By Danielle Russell ’25

For most of its history, North Carolina has been divided over the issues of slavery and secession, and the intertwined legacy of both. Although the state’s motto that it was “First at Bethel, Farthest to the Front at Gettysburg and Chickamauga, and Last at Appomattox” suggests North Carolina stood as a stalwart supporter of the Confederacy, the state’s history is far more complicated.

Beginning in the eighteenth century, the coastal region represented the center of the state’s plantation agriculture, which was dominated by the socio-political influence of wealthy planters, though it was also home to many members of the working class and the enslaved. By 1791, a little more than a third of all North Carolinian families held enslaved people, and by the start of the Civil War, African Americans, free and enslaved, constituted a third of the state’s population. Most of the state’s enslaved people labored on plantations that produced wheat, rye, corn, oats, rice, tobacco, peas, beans, and potatoes (1850 North Carolina Census of Agriculture). In some coastal counties, with the exception of Tyrell, Hyde, and Carteret, between forty and fifty percent of the population was enslaved (Carbone 87). The state’s central Piedmont region, though still containing thousands of enslaved individuals, possessed a notable anti-slavery Quaker population (Barrett 3). Although the western region had a lower proportion of enslaved individuals, four routes through the mountainous region were frequently utilized by slave traders to transport enslaved people farther south, to South Carolina and Alabama (“Chattel Slavery in the Appalachians of North Carolina”). Some of this region’s inhabitants may have opposed slavery, but they turned a blind eye to their region’s participation in the slave trade.

Following Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831, in nearby Southampton County, Virginia, many North Carolinians feared a similar event, and enacted legislation to prevent such an occurrence. Laws passed just a year earlier, in 1830, made it illegal to educate enslaved individuals, while an 1835 law prohibited free African Americans from public preaching, voting, and attending school (“The Growth of Slavery in North Carolina”). The state’s large enslaved population stoked constant dread of a revolt, and Nat Turner’s Rebellion escalated those fears.

Politically, between 1836 and 1850, the Whig Party, with a vocal anti-slavery minority, dominated the state’s politics (Carbone 1). Nonetheless, by 1850 many of North Carolina’s yeoman farmers and non-slave owners grew frustrated by the slaveholding class’s dominance in state politics. By 1860, a staggering eighty-five percent of men in North Carolina’s General Assembly owned slaves (Leloudis and Korstad, 6). These men, who possessed direct financial, social, and political stakes in slavery passed legislation that protected the institution and further privileged its white participants. In the decade before the Civil War, the white farmers of the western and Piedmont regions, which contained fewer enslaved people (though who admittedly still held a stake in slavery), revolted against the General Assembly. These men demanded the revocation of the property requirement necessary to vote and insisted on the passage of an ad valorem tax on the enslaved property of the state’s slaveholding elites. Although their first requirement was met in 1856, it was not until five years later, in 1861, that the General Assembly voted on the tax.

Despite the farmers’ dissatisfaction, the state remained committed to slavery’s continuation, with white non-slaveholders in the eastern regions benefitting from the system’s “hiring out” practices as well as the racial privilege that the continuation of slavery would always protect for whites. Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln did not even appear on North Carolinian ballots in the election of 1860, and the state voted strongly for Southern Democratic candidate, John C. Breckinridge, who received roughly 50.5% of the popular vote. John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party garnered about 46.7% of the vote, a testament to many North Carolinians’ Union sympathies. Northern Democratic candidate, Stephen Douglas earned the remaining 2.8% (The American Presidency Project).

On May 20, 1861, North Carolina seceded and joined the Confederacy. Although initially hesitant, the state’s overall dedication to the protection of slavery and the threat President Lincoln posed to the institution ensured that the state could not remain in the Union. However, even still, North Carolina was not quite the stalwart Confederate state that the “First at Bethel” motto tries to make it seem.

In 1862, Zebulon B. Vance, an ardent supporter of slavery, yet initially hesitant secessionist member of the Conservative Party, won the gubernatorial election. Vance and other North Carolinians were incensed by many of the Confederacy’s policies, including conscription, the tax-in-kind law that placed a ten percent tax on all agricultural products, the impressment policy that permitted Confederate officers to seize all property, including enslaved people, for the Confederate war effort, and the “Twenty Negro Law,” which exempted men who enslaved more than twenty people from military service. Vance was particularly angered by Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s refusal to appoint any North Carolinians to the rank of general. Given the state’s slowness to secede, Davis doubted North Carolina’s loyalty to the Confederate cause (Carbone 121-122). Davis’s open suspicion further increased North Carolinians’ frustrations with the Confederate government.

Davis may have been right to suspect North Carolinians of harboring Union sympathies. North Carolinian troops deserted at a higher rate than soldiers from any other state, and in the western and Piedmont regions, a group known as the Order of the Heroes of America, comprised of Quakers and Union sympathizers, aided Confederate deserters in avoiding detection by the authorities (Leloudis and Korstad, 7). The state also raised four white Union regiments, including the notorious 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry, recruited from the western portion of the state, and four black Union regiments, recruited principally from the Union-occupied coastal region, which made up the majority of Colonel Edward Wild’s “African Brigade” (Carbone 99).

Further demonstrating the divisions within North Carolina, William Woods Holden, the editor of the popular Raleigh-based North Carolina Standard, printed numerous articles that called for peace negotiations. Holden later ran against Zebulon Vance in the 1864 gubernatorial election. Although he lost, Holden won in Johnston, Wilkes, and Randolph Counties, three counties in the central Piedmont region (Carbone 123). While not strong enough to overrule most Tar Heels’ dedication to the protection of slavery, and by extension, the Confederacy, Holden’s failed run for governor represented the enthusiastic vocal minority of Union sympathizers.

Over the course of the war, roughly 138,000 North Carolinians fought in the Union and Confederate armies. About 130,000 men fought for the Confederacy, while 8,000 fought for the Union, about 5,000 of whom served in the United States Colored Troops. North Carolinians fought at all of the major eastern-theater battles during the conflict. By the war’s end, nearly 40,500 of the 138,000 died, which comprised a staggering 6% of the state’s population. Although the state furnished two noteworthy Union officers, Rear Admiral Henry H. Bell and Brigadier General John Gibbon, it provided a larger number of high-ranking Confederate officers. These men included Gen Braxton Bragg, Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk, Major Generals D.H. Hill, Robert F. Hoke, William Dorsey Pender, and Stephen Dodson Ramseur, and Brigadier Generals Lewis A. Armistead, and J. Johnston Pettigrew. Wilmington’s harbor, with access to the Atlantic Ocean and overseas ports, and often used by blockade runners, was vital to the state’s ability to secure supplies, and thus made a prime target for the Union Army. Although not as important as Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, rice and corn grown in North Carolina represented key food sources. The most significant battles fought in North Carolina include the following:

- August 28-29, 1861 – Battle of Hatteras Inlet Batteries

- March 14, 1862 – Battle of New Bern

- December 14, 1862 – Battle of Kinston

- December 17, 1862 – Battle of Goldsborough Bridge

- December 7-27, 1864, and January 13-15, 1865 – Battles of Fort Fisher

- March 7-10, 1865 – Battle of Wyse Fork

- March 16, 1865 – Battle of Averasboro

- March 19-21, 1865 – Battle of Bentonville

The imposing task of Reconstruction began almost immediately after Confederate General Joseph Johnston surrendered to Union General William T. Sherman at the Bennett house on April 26, 1865. In May, President Andrew Johnson appointed William W. Holden as provisional governor of North Carolina. This fateful move had a defining impact on the state’s post-war period. Although Holden desired to guide the state towards more progressive policies, his appointment and later actions in office launched a series of retaliatory efforts by the state’s former Confederates. These individuals sought to prevent any change in the state’s antebellum policies of whites’ legal and social supremacy. At the state’s 1865 convention, the first step in Reconstruction, the state’s representatives demanded the immediate expulsion of all United States Colored Troops from North Carolina (Alexander, “Convention of 1865”).

A year later in 1866, the General Assembly passed a series of Black Codes that prohibited black suffrage, required black men to have a license to carry a weapon, established death as the punishment for a black man’s sexual assault of a white woman, prohibited black men from testifying against whites in court unless they were the plaintiff or defendant, outlawed interracial marriage, forbid blacks from returning to North Carolina if they resided outside the state for more than ninety days, and asserted that a black man charged with vagrancy would be forcibly hired out (“Black Codes in North Carolina, 1866”). In the wake of Confederate defeat and faced with the possible disintegration of their slavery-based racial hierarchy, North Carolinian white men wished to legally assert what they viewed as their supremacy in all matters, and in turn, black men’s total inferiority.

Despite the General Assembly’s attempts to uphold white supremacy, in 1868, William W. Holden was elected governor, and the biracial Republican Party won seven congressional seats and two-thirds of the seats in the state legislature (Leloudis and Korstad, 10). In retaliation for these imposed advances towards racial equality, the Ku Klux Klan, led in North Carolina by William L. Saunders, unleashed a reign of terror that worsened until 1870, and culminated in a statewide event known as the Kirk-Holden War. After the lynching of African American politician and Union veteran, Wyatt Outlaw, and Republican Senator, John W. Stephens, who was known for working with the Freedmen’s Bureau, Governor Holden appointed Colonel George Washington Kirk, the previous commander of the infamous Third North Carolina Mounted Infantry, to command the state’s militia. Colonel Kirk and his command of more than three hundred men arrested over one hundred men in Alamance and Caswell counties, part of the northern Piedmont region and the seat of Klan activity. After months of further violence and legal proceedings, most of those Colonel Kirk arrested were eventually freed. Incensed by Governor Holden’s actions, Frederick N. Strudwick, a member of North Carolina’s House of Representatives and a Klan leader in Orange County, introduced the articles of impeachment. Holden’s impeachment on charges of unlawful detention, inciting civil war, and subversion of personal liberties, marked the beginning of the end of North Carolina’s progressive politics. With Holden’s impeachment, the state’s former slaveholders seized the opportunity to enact regressive legislation that reasserted their social and political dominance.

By 1874, the Democrats regained total control of the General Assembly and introduced more than thirty amendments aimed at segregation and reinforcing white supremacy (Leloudis and Korstad, 12). Earlier Republican successes meant that between 1877 and 1900, forty-three black North Carolinians served in the state’s House of Representatives, eleven in the state’s Senate, and four in the United States House of Representatives (Leloudis and Korstad, 13). However, these successes were quickly wiped out by the Democratic Party’s decades-long rule in the state.

Despite the presence of wartime Unionist sentiment, by 1898, with the Democratic Party maintaining its iron-tight grasp over politics, white supremacist legislation dominated North Carolinian governments at the local and state level (Leloudis and Korstad, 19). The election of 1872 represented the last nineteenth century presidential election where North Carolina largely supported the Republican candidate. Regardless of the state’s overwhelming support for the Republican candidate, former Union General Ulysses S. Grant, as former Confederates in the General Assembly began to pass legislation meant to disenfranchise blacks and poor whites, the tide swiftly turned. The swath of Republican sympathies that flourished across the state during Reconstruction quickly receded when met by the overwhelming crush of discriminatory legislation passed in the wake of Reconstruction’s demise. Beginning in the election of 1876, nearly every county in the state voted strongly in favor of the Democratic Party. What remained of the Republican voters in North Carolina was relegated to the northern portion of the coastal region and a handful of counties scattered throughout the state. The Piedmont saw the most dramatic change. Home to a large proportion of the state’s black population, the region’s voters experienced the most significant disenfranchisement as former Confederates sought to reclaim the region. Legal attempts to establish political power as a whites-only privilege was shadowed by violence, as in 1898, when ex-Congressmen, Alfred M. Waddell led a mob of armed white men who burned the printing office of Wilmington’s sole black newspaper, murdered roughly thirty black citizens, and expelled the city aldermen, establishing a new board with Waddell as the leader (Leloudis and Korstad, 22). An extension of the post-war Klan violence, Waddell’s threatening public example went unpunished, and legislation passed later that year further disenfranchised blacks and poor whites.

At the dawn of the twentieth century and well into the 1940s, Democrats further entrenched segregation and white supremacy in North Carolinian society. However, beginning in the 1940s, racial equality movements increased in their strength and frequency. Stemming from the World War II era Double V program, the Congress of Industrial Organization’s Food, Tobacco, Agricultural, and Allied Workers Union sponsored a campaign that provided citizenship and literacy classes, and ultimately resulted in Reverend Kenneth R. Williams’s 1947 election to the Winston-Salem Board of Aldermen. Reverend Williams’s victory was a monumental one in the state’s twentieth century history. Between the 1890s and 1947, Reverend Williams was the only black politician to defeat a white politician at the local or state level (Leloudis and Korstad, 39).

With Reverend Williams’s election and the beginning of the civil rights movement, black politicians began to slowly gain positions in local offices in the Piedmont and western regions. The coastal region, the state’s most densely concentrated area of enslaved individuals during the antebellum period, remained steadfast in its segregationist policies. Only after the February 1, 1960, Greensboro Woolworth’s sit-in led by Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Joseph McNeil, along with subsequent sit-ins elsewhere throughout the state, did segregation begin to crumble.

Just a year later marked the start of the Civil War centennial, and North Carolina’s state commission quickly developed a plan to honor its Confederate past. The twenty-five-member commission focused their efforts on programs and visuals most likely to instill youth with what it termed “a deep appreciation for the heritage which is theirs as Tar Heels” (Larson, 196). The commission’s decided its committees would focus on holding a Confederate Festival, local memorial events that featured recreations of historical events, written and audio-visual publications, preserving documents and other artifacts, educational programs for schools, and cemetery, monument, and historic site preservation (Larson, 196). The Confederate Festival served as the crown jewel of the commission’s intended plans. A two-day event, the festival, held in spring 1961, included a parade, performances by a band of Confederate reenactors, various receptions, and its main event was a Civil War style costume ball. The festival epitomizes the state’s commemorative efforts, which adopted a romanticized view of the Confederacy that ignored the state’s Union sympathies and the centrality of slavery in the state’s history. Instead, the commission inaccurately depicted Confederate soldiers and civilians as stalwart defenders of states’ rights, portraying the soldiers as dashing cavaliers and the civilians as loyal supporters of their brave heroes at the front. This Lost Cause view permeated all aspects of the centennial in North Carolina as civil rights era Carolinians sought to vindicate their ancestors’ condemnable cause and ensure its permanent place of honor among future generations. The commission’s most ambitious plan was its fascination with Confederate blockade runners. In one of its most expensive endeavors, it raised the CSS Neuse, which the Confederate army scuttled to prevent its capture by the Union Army in March 1865. After the costly removal of artifacts found in its hull, the Neuse was raised in 1963, and placed on display in Kinston (United States Civil War Centennial Commission, 54).

Much like Governor Holden’s election almost one hundred years prior, Terry Sanford’s election to governor in 1963 represented a vital development in North Carolina’s progress towards racial equality. Just four days after Alabama Governor George Wallace delivered his inaugural address in which he declared “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever,” Sanford gave his address that referenced the Emancipation Proclamation and urged an end to the state’s rampant “unfair discrimination” (Leloudis and Korstad, 72). Although met with firm resistance from the KKK and other groups, Governor Sanford’s North Carolina Fund, which sponsored a series of anti-poverty programs spread throughout the state’s three regions, served as another step towards dismantling the state’s long-entrenched racial hierarchy. However, many in the state continued to resist Governor Sanford’s changes in policy, and two men, North Carolina Senators Samuel J. Ervin Jr. and B. Everett Jordan, helped lead the fight against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Leloudis and Korstad, 75).

Regardless of the rebellion against racial equality, in 1989 a record-breaking nineteen black legislators were elected to the state’s General Assembly, and just two years later, Dan Blue was elected to speaker of the North Carolina House of Representatives (Leloudis and Korstad, 83). To this day, Blue’s position represents the highest office held by a black politician in North Carolina. It stands as a landmark achievement, considering that just ninety-three years earlier, Alfred Waddell and his mob prevented Wilmington’s black population from exercising political authority and used excessive violence to discourage resistance.

Throughout the 1990s, the state remained divided politically, and most elections were won by exceedingly slim margins (Leloudis and Korstad, 94). While originally one of the lowest ranked states for voter participation, the Democratic Party’s efforts to increase voter participation between 1992 and 2009 meant that, by 2012, the year the state’s last Confederate monument was erected, the state had the eleventh highest voter participation (Leloudis and Korstad, 97).

Unlike the state’s well-funded and thoroughly planned celebration for the Civil War centennial, the General Assembly did not allocate any funds for the commemoration of the sesquicentennial. Instead, the events were coordinated by smaller, independent organizations. Additionally, instead of the grand, public events, like the Confederate Festival held for the centennial, most of North Carolina’s sesquicentennial plans focused on less-biased museum exhibits on North Carolinian women and African Americans, or conferences (Phelps and Swain). While the centennial, heavily influenced by the Lost Cause, witnessed the erection of four Confederate monuments within the state, pro-Confederate sentiment dissipated in the following fifty years, and only two Confederate monuments were erected during the sesquicentennial. Although the state has increasingly begun to grapple with its ties to the Confederacy, traces of Confederate sympathies remained well into the twenty-first century and were reflected in the sesquicentennial. The key difference was that, during the sesquicentennial, those promoting the perpetuation of the moonlight and magnolias view of the state’s history belong to separate organizations not linked to the state or federal government.

From its very founding North Carolina has stood as a divided state, torn between its loyalty to the slaveholding south, its Confederate past, and the Union’s promise of freedom.

Confederate Monuments

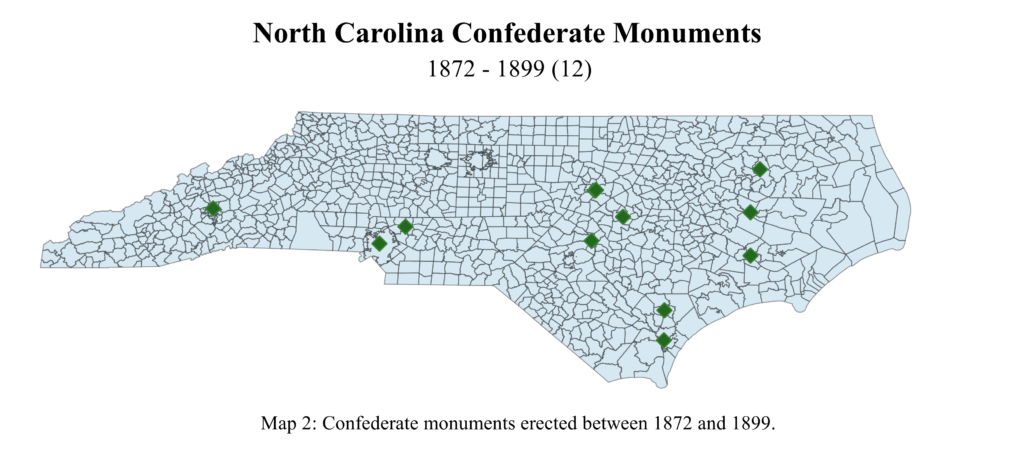

1872-1899

By the end of the nineteenth century, North Carolinians erected twelve Confederate monuments. Most of these were in the Piedmont, likely due to the region’s strong support for the Confederacy. Only one monument was erected in the mountainous western region, a testament to that area’s conflicting loyalties.

- Non-specific honoree monuments: 10

- Specific honoree monuments: 2

- Honorees: Zebulon Vance and Co. K, 3rd North Carolina Infantry

- Dedicated by Ladies Memorial Associations or the United Daughters of the Confederacy: 7

- Dedicated by the United Confederate Veterans or the Sons of Confederate Veterans: 2

- Dedicated by private individuals: 2

- Dedicated by the state of North Carolina: 1

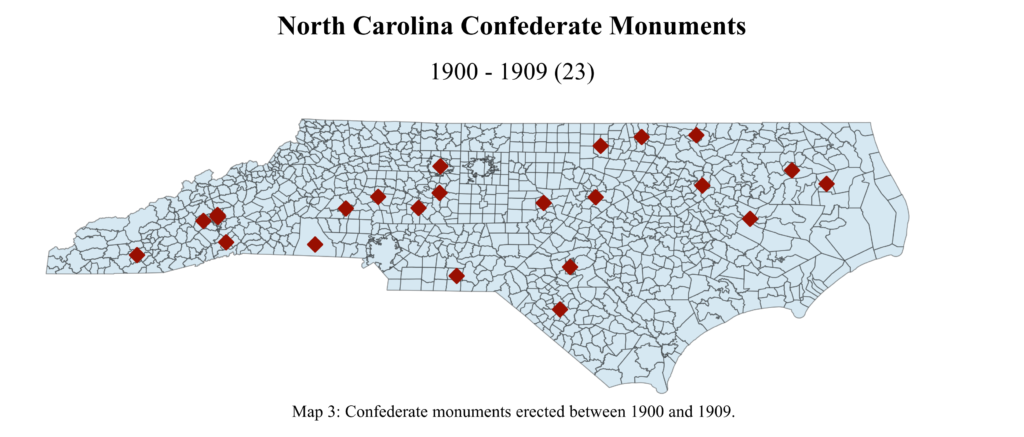

1900-1909

In the first nine years of the twentieth century, as monumentation became increasingly popular, twenty-three monuments were erected across the state, though most were centered in the Piedmont. These monuments likely served as a statement of continued dedication to the Confederacy, but also acted as an important symbol of whites’ social and political power in the region with the largest black population. While Republicans increased their majorities in western counties, former Confederates erected four more monuments in the south-western counties, perhaps in retaliation for their political losses.

- Non-specific honoree monuments: 21

- Specific honoree monuments: 2

- Honorees: Zebulon Vance and Company I, 25th North Carolina Infantry

- Dedicated by Ladies Memorial Associations or the United Daughters of the Confederacy: 17

- Dedicated by the United Confederate Veterans or the Sons of Confederate Veterans: 1

- Dedicated by private individuals: 5

- Dedicated by the state of North Carolina: 0

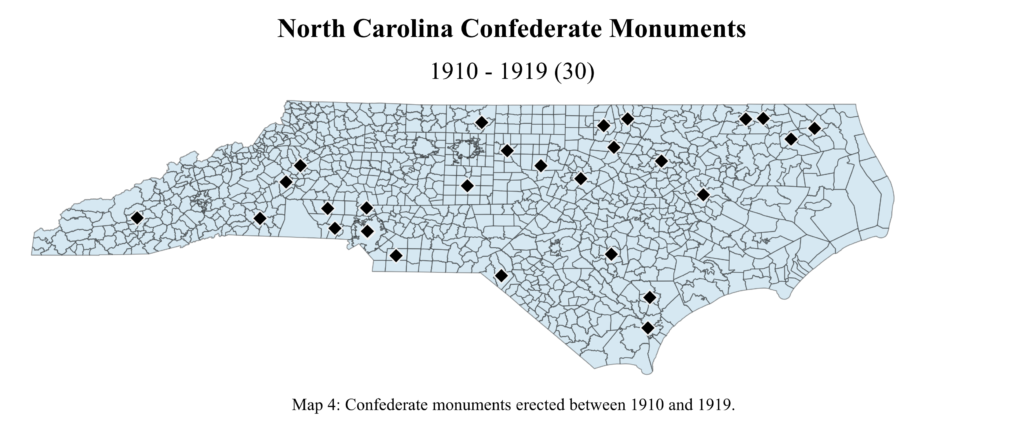

1910-1919

Over the course of just nine years, from 1910 to 1919, North Carolinians erected thirty monuments, with most dedicated in the Piedmont, and just one in the western region. Sixteen of these monuments were dedicated between 1910 and 1912. During the 1912 Presidential election, all but ten counties had strong Democratic majorities compared to prior years, which could explain the high rate of monument dedications during this period.

- Non-specific honoree monuments: 27

- Specific honoree monuments: 3

- Honorees: George Davis, Henry Lawson Wyatt, Thomas J. Jackson

- Dedicated by Ladies Memorial Associations or the United Daughters of the Confederacy: 21

- Dedicated by the United Confederate Veterans or the Sons of Confederate Veterans: 1

- Dedicated by private individuals: 8

- Dedicated by the state of North Carolina: 0

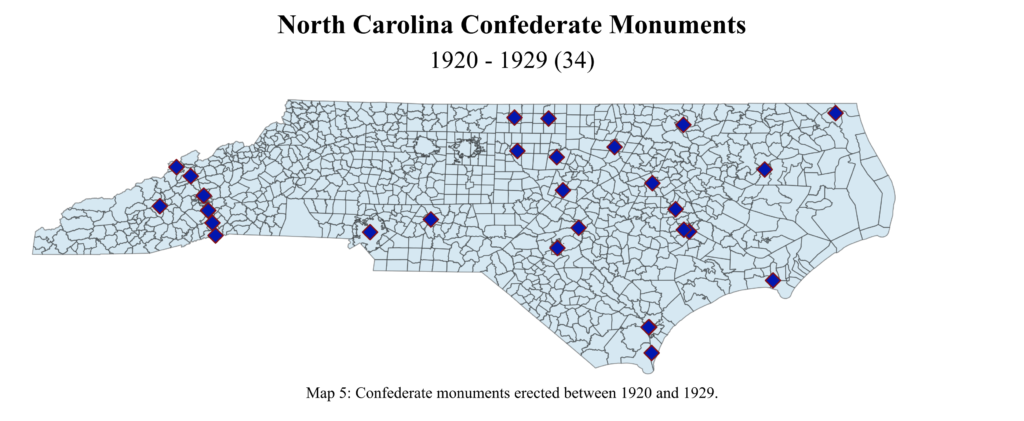

1920-1929

The Democratic Party and former Confederates maintained their majorities from 1920 to 1929, and the rate of monument dedications continued, with an increase of only four monuments compared to the prior decade. Unlike previous decades, this period represented a significant shift with the erection of seven monuments in western counties. However, the monuments mostly remained concentrated in the Piedmont.

- Non-specific honoree monuments: 20

- Specific honoree monuments: 14

- Honorees: Robert E. Lee (6). Robert Hoke, William Kenan Sr., Junius Daniel, William Henry Hardy, Herman Frank Arnold, Dan Emmett, Albert Pike, Zebulon Vance

- Dedicated by Ladies Memorial Associations or the United Daughters of the Confederacy: 24

- Dedicated by the United Confederate Veterans or the Sons of Confederate Veterans: 1

- Dedicated by private individuals: 3

- Dedicated by county historical commissions: 4

- Dedicated by the state of North Carolina: 2

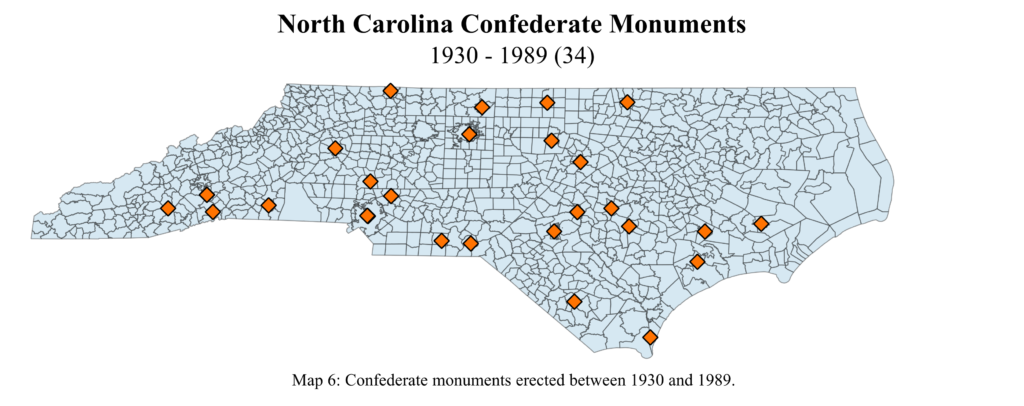

1930-1989

As the Civil War generation died off, the rate of dedications slowed tremendously. Unlike the nine-year time span from 1920 to 1929, which witnessed the dedication of thirty-four monuments, in the nearly sixty years from 1930 to 1989, just thirty-four monuments were dedicated in North Carolina. Twenty-seven of these monuments were dedicated between 1930 and 1960. Once more these monuments were located mostly in the Piedmont. Even the sesquicentennial did not seem to increase dedications. Between 1961 and 1965, North Carolinians dedicated four Confederate monuments.

- Non-specific honoree monuments: 23

- Specific honoree monuments: 11

- Honorees: Jefferson Davis (4), Orren Randolph Smith, Henry Timrod, Robert E. Lee, Judah P. Benjamin, Samuel A’Court Ashe, Matthew F. Maury, 64th North Carolina Infantry

- Dedicated by Ladies Memorial Associations or the United Daughters of the Confederacy: 23

- Dedicated by the United Confederate Veterans or the Sons of Confederate Veterans: 4

- Dedicated by private individuals: 2

- Dedicated by unknown groups: 1

- Dedicated by the state of North Carolina: 1

- Dedicated by other states: 2 (these monuments were dedicated by Texas and South Carolina on the Bentonville Battlefield)

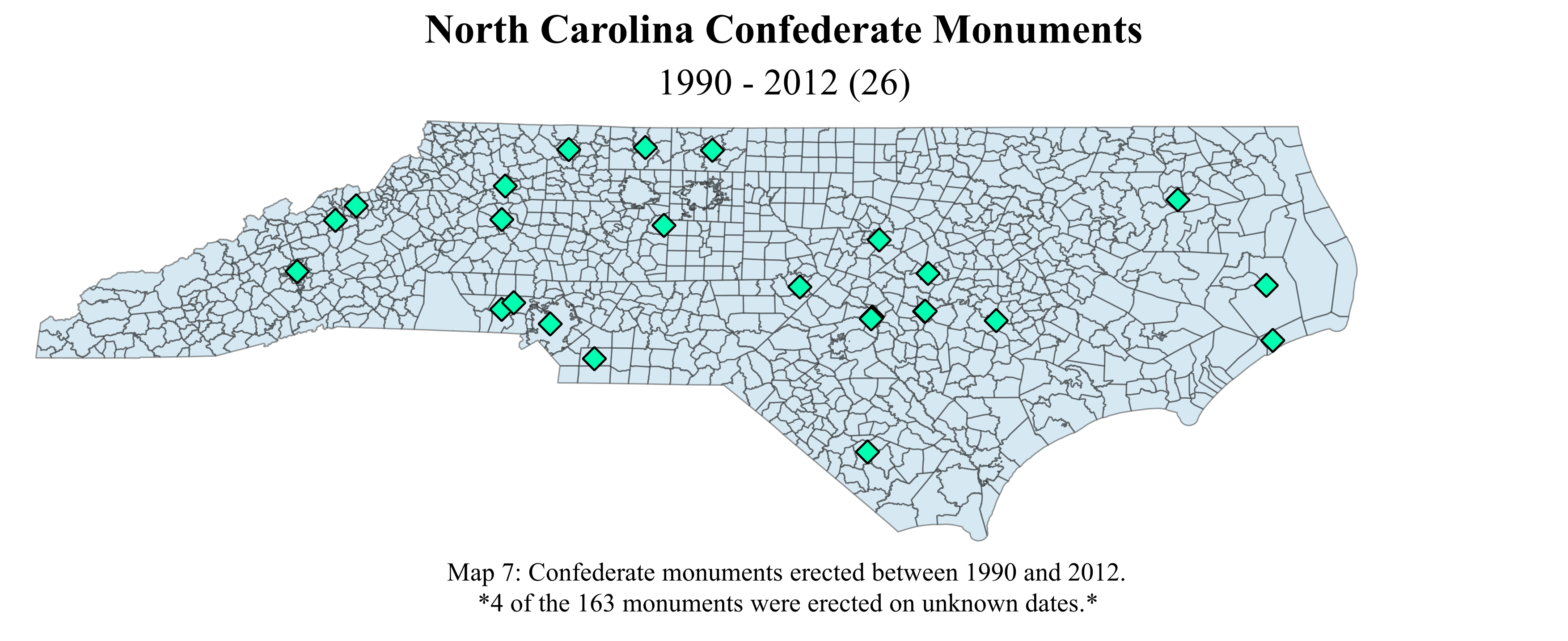

1990-2012

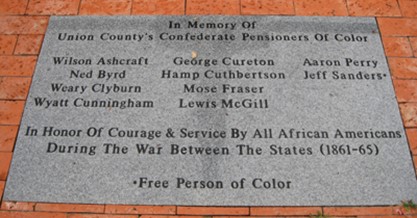

Between 1990 and 2012, North Carolinians dedicated twenty-six monuments, twenty-one of which were erected after 2000, suggesting significant Confederate sympathies were present well into the twenty-first century. The last monument was dedicated in the state on December 8, 2012, by a committee that included several members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. It was dedicated to “Union County’s Confederate Pensioners of Color,” a description that erroneously described blacks’ contributions to the Confederate war effort as voluntary, rather than forced.

- Non-specific honoree monuments: 20

- Specific honoree monuments: 6

- Honorees: Edenton Bell Battery, McLaws’ Division, Taliaferro’s Division, Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, H.L. Hunley

- Dedicated by Ladies Memorial Associations or the United Daughters of the Confederacy: 2

- Dedicated by the United Confederate Veterans or the Sons of Confederate Veterans: 15

- Dedicated by private individuals: 6

- Dedicated by unknown groups: 2

- Dedicated by city/county historical commissions: 1

- Dedicated by the state of North Carolina: 0

Union Monuments

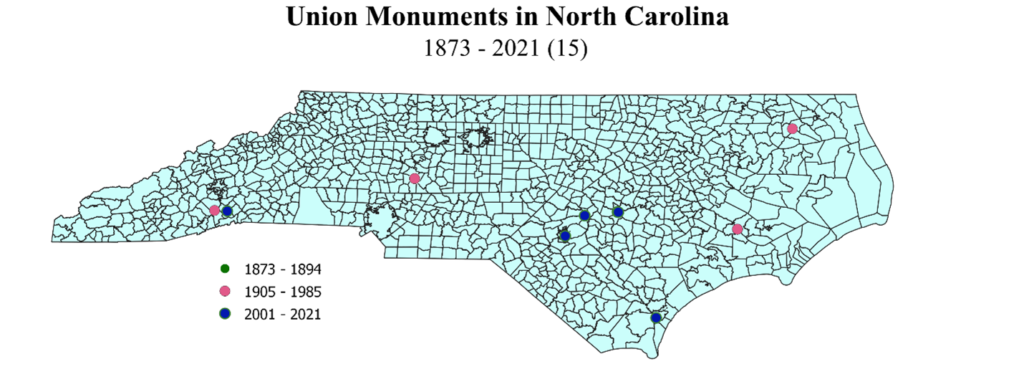

The first Union monument in North Carolina was erected by Congress to the memory of the Union dead in Salisbury National Cemetery in 1873. Although they are roughly distributed throughout the state, most Union monuments were erected by state governments in New Bern National Cemetery, Salisbury National Cemetery, or by private organizations at the Bentonville and Averasboro Battlefields. The last Union monument, which was dedicated to United States Colored Troops (USCTs), was erected in 2021, nine years after the dedication of the state’s last Confederate monument. North Carolina has two monuments dedicated to USCTs. The first was dedicated by the United Daughters of Veterans in 1910, in the state’s northern coastal region. Most Union monuments in North Carolina were dedicated to regiments or states, rather than to individuals.

- Non-specific honoree monuments: 4

- Specific honoree monuments: 11

- Honorees: 14th, 15th, 17th, and 20th Corps, United States Colored Troops (USCTs), Massachusetts dead, Rhode Island dead, Pennsylvania dead, Maine dead, 9th New Jersey Infantry, 123rd New York Infantry, Captain Alexander McRae, 15th Connecticut Infantry, 20th Corps

- Dedicated by the Daughters of Union Veterans or the United Daughters of Veterans: 1

- Dedicated by the Sons of Union Veterans: 1

- Dedicated by other descendant groups: 1

- Dedicated by private individuals: 2

- Dedicated by museums: 2

- Dedicated by county historical commissions: 1

- Dedicated by other states: 6 (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island)

- Dedicated by Congress: 1

Analysis

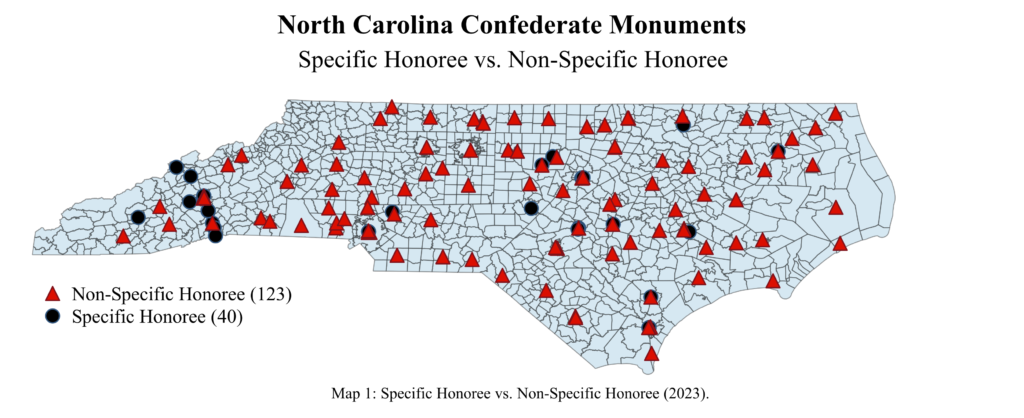

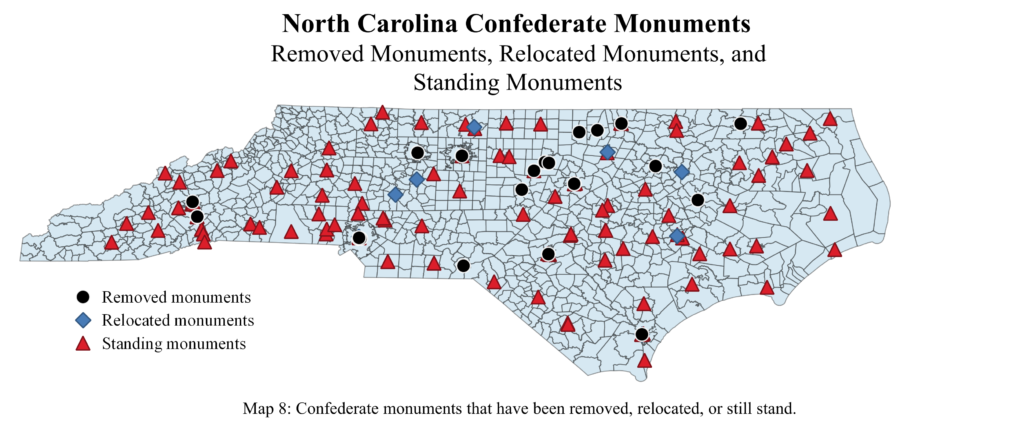

The first Confederate monuments in North Carolina were erected by local memorial associations in 1872, establishing a trend that continued for more than a century. As former Confederate men focused their attention on reclaiming their dominance in the state’s political arena and overturning Republican progress in the early years of Reconstruction, women dedicated monuments that cemented the state’s Confederate legacy in the public sphere for generations to come. Women held a near monopoly on the state’s monumentation efforts well into the twentieth century. It was not until the last wave of monument dedications, from 1990-2012, that male-dominated organizations like the United Confederate Veterans or Sons of Confederate Veterans outpaced the vigorous monumentation dedications of the Ladies Memorial Associations and United Daughters of the Confederacy. This trend tracks with that of other former Confederate states wherein women, who were often seen as nonpolitical – and thus, non-threatening – actors were often asked with perpetuating the memorialization of southern men’s martial prowess and the Confederacy as a whole. However, the distinct stronghold that North Carolina women held on monumentation efforts until the late 20th century may be due to other reasons unique to the state that are rooted in North Carolina’s war-time history. For example, the state’s ninth monument, dedicated in 1892, commemorated the service of Company K, 3rd North Carolina Infantry, from which several deserters were executed in the Army of Virginia’s largest execution in September 1863. In the wake of the execution, newspapers had warned against women urging their husbands and sons to desert from their regiments and return home and blamed them for any demoralization that the soldiers felt. Perhaps in the early years after the war, women’s efforts were an attempt to vindicate these widespread wartime accusations that they were responsible for the state’s notably high desertion rate. Even in the postwar years, many former Confederates viewed this desertion rate, along with the state’s divided loyalties, as proof of the state’s ultimate disloyalty to the Confederacy. It is possible that North Carolinians utilized monumentation as vindication – proof that, even after the war, they remained fiercely loyal to the Confederacy.

The vast majority of the state’s Confederate monuments stand near courthouses, and are scattered across the state. Such prominent positioning emphasizes local communities’ pride in their Confederate heritage, but also displays the strong intertwining of Confederate social, cultural, and political ideologies within the post-war southern legal system – a powerful statement attesting to former Confederates’ reconquest of state politics in the post-Reconstruction era. Unlike other former Confederate states, where monuments were concentrated in specific regions, monuments rose across North Carolina. However, some areas of the state, like the northwest, the southwest, and the eastern coastal region, experienced higher levels of monumentation. Western North Carolinians possessed divided loyalties, which in other states, led to fewer postwar Confederate monuments. However, in North Carolina, these areas endured numerous raids by Union regiments, such as those by the 2nd and 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantries, units comprised of a wide variety of men including Native Americans and Confederate deserters. Although most men of the 2nd and 3rd were from western North Carolina, others, like the 3rd’s Colonel, George Washington Kirk, were from eastern Tennessee. Pro-Confederate inhabitants of western North Carolina despised these regiments, largely for their inclusion of non-white soldiers and Confederate deserters. After the war, members of these regiments were unwelcome in their former homes, having fought against their neighbors. Perhaps in response to this miniature civil war and the disloyalty of their neighbors, former Confederates ensured western North Carolina became a scene of heavy monumentation as a final rebuff of Unionist attempts to take over the region. Along the coastal region, ex-Confederates erected monuments to reclaim the land formerly occupied by Union soldiers and serving as a former haven for enslaved people seeking to escape the cruelties of slavery. Unlike the western and easternmost regions, the wave of monumentation did not reach the east-central region until the early twentieth century, likely because of the region’s dominant Quaker population. Outnumbered by the anti-slavery contingent, ex-Confederates there lacked support for their monumentation efforts.

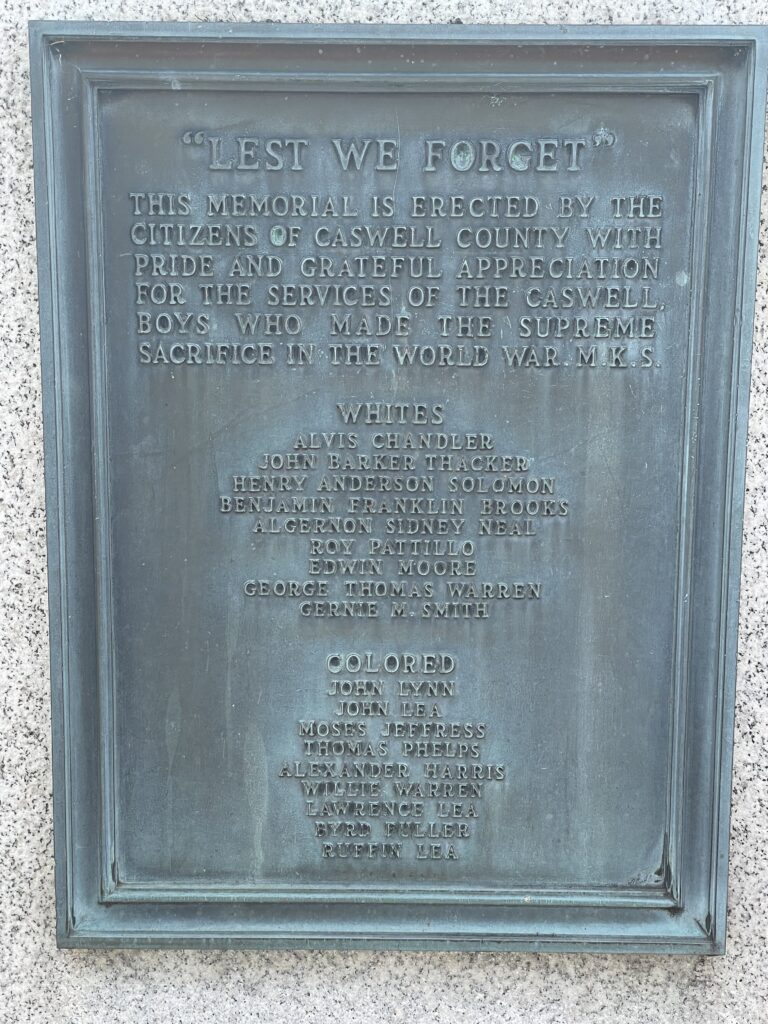

The rate of monument dedications increased rapidly in the first portion of the twentieth century, aligned with national fervor that swept the country at the time. As the overall number of monuments increased, so did the number of monuments with specific honorees. As the Civil War generation faded away, North Carolinians sought to forever enshrine the heroes of their Confederate past. Those heroes included the most obvious Confederate national candidates, President Jefferson Davis, General Robert E. Lee, as well as wartime Governor Zebulon Vance, North Carolinian General Robert Hoke, and Henry Lawson Wyatt, the first North Carolinian soldier killed in battle. While Carolinians wished to honor the idols of the Confederacy as a whole, they also sought to venerate their local luminaries. As racial animosity and the implementation of Jim Crow laws increased, North Carolinians erected Confederate monuments in conspicuous public spaces to remind the black population of the control exercised by local and state governments that were dominated by former Confederates. The rise of patriotic fervor amidst the United States’ entrance into World War I added both to the state’s desire to yoke a unique brand of Confederate martial valor to 20th-century American patriotism, and, in turn, to discriminatory rhetoric toward black Americans. Outside the Piedmont’s Caswell County Courthouse in Yanceyville, roughly fourteen miles from Virginia’s southern border, residents erected a World War I monument next to a Confederate monument. Although the World War I monument acknowledged black veterans from Caswell, it listed them separately from white veterans. The conspicuous placement of both monuments, in front of the courthouse where the Ku Klux Klan assassinated State Senator John W. Stephens in 1870, for his association with the Republican Party, the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the Union League, was intended to further reinforce the connection Carolinians drew between the Confederate socio-political hierarchy, the post-war legal system, and the unique martial power and prowess of white Tarheels, both at home and abroad. These monuments thus served as constant reminders that the whites in control of the state viewed their black neighbors as second-class citizens.

Even the economic hardship of the Great Depression failed to diminish North Carolina’s zeal for Confederate monumentation. Dedications continued throughout the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. During this time, Black residents were mobilizing in increasing strength around the issue of civil rights. The civil rights movement, whose origins in the state grew out of Reverend Kenneth William’s successful 1947 campaign to join the Winston-Salem Board of Aldermen, as well as the string of sit-ins that began in Greensboro in February 1960, threatened whites’ monopoly on socio-political power. In turn, the new generation of Carolinians likely erected additional Confederate monuments to publicly reassert their claims to that power, just as their parents and grandparents had at the turn of the century.

Although North Carolinians continued to glorify the Confederacy during the Civil War Centennial with the addition of five new monuments, dedications slowed dramatically and ceased entirely after 2012, just one year into the sesquicentennial, with Union County’s “Memorial for Confederate Pensioners of Color.” This downward trend in monument dedications followed the nationwide decrease in interest in the Civil War following the Centennial. At the same time, the state’s most populous cities expanded dramatically. In 1960, 201,564 people lived in Charlotte, though the city grew to 241,178 people by 1970. Although just 85,768 people lived in the state’s capital at Raleigh in 1960, by 1970, the city’s population surged to 121,577. Durham and Winston-Salem experienced similar increases of roughly 20,000 people. During the same period, Greensboro’s population increased by more than 30,000 people. As these cities grew and diversified, their inhabitants’ support for Confederate monumentation decreased over the last half of the twentieth century. While North Carolinians continued to erect monuments across the state, albeit in smaller numbers, a significant portion were dedicated in the western and Piedmont regions, perhaps in response to the noticeable increase of Asian, Hispanic, and black populations in those areas. Unlike the similarly diversifying, yet more cosmopolitan urban centers, as these more rural and former predominantly white regions diversified in the latter half of the twentieth and early portion of the twenty-first centuries, some white communities visually reemphasized their allegiance to the Confederacy with the creation of new Confederate monuments.

Notably, over North Carolina’s 140-year period of dedications, the state legislature erected just four of the more than 150 monuments. Memorialization efforts were a predominately local task, and thus the projects exemplified local interest. Monuments with non-specific honorees consistently outnumbered those with specific honorees, suggesting local communities were far more interested in honoring a broader swath of Confederate soldiers, rather than dist5inct individuals. These monuments were meant to represent the “common” North Carolina Confederate.

The circumstances behind the dedication of North Carolina’s Union monuments are completely contrary to those of Confederate monuments. Most Union monuments were dedicated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, amidst widespread national memorialization efforts. These monuments were dedicated by other states to specific regiments or soldiers, and are located on battlefields or in cemeteries, unlike the more public Confederate monuments. However, five monuments, dedicated in 1910, 1985, 2008, 2013, and 2021, were placed in public spaces. Two of the seven 20th-century and three of the five 21st-century monuments were dedicated in public spaces, like courthouse lawns, museums, and town squares. Given former Confederates’ aggressive takeover of state and local politics during and after Reconstruction, proposed Union monuments likely faced considerable opposition. As time wore on and the Civil War generation died out, groups and private individuals faced less opposition in the construction of Union monuments.

Although former Confederates in the state legislature had dedicated four Confederate monuments in the post-war period, they refused to construct a single Union monument. Rather, Unionist groups such as the United Daughters of Veterans and northern state governments took the reins of such efforts, particularly focusing on adorning the National Cemeteries and battlefields that commemorated two of the last major battles in the state. While Averasboro was an inconclusive battle, it still garnered Unionist support for monumentation. Meanwhile, the decision to place monuments on the Bentonville battlefield, where General Sherman’s Union Army defeated Confederate General Johnston’s forces in the final large-scale battle of the war underscores the Union’s ultimate victory: While the Confederates won the war of memory, the Union won the war itself and reunited the nation. Ultimately, despite the state’s divided wartime loyalties, Confederate monuments far exceeded the state’s fifteen Union monuments, even though Union monuments were dedicated over a far larger period. As a result, the intense, pro-Confederate commemorative efforts make the state, and its people appear far more loyal to the Confederacy than it seemed during the war.

Though on the winning side of history, North Carolinian Unionists lost the war of memory. Almost in a second phase of Democrats’ crusade to retake the state from progressive Republican policies in the immediate postwar period, Confederate supporters in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries ensured that the most dominant visible traces of the state’s past supported their false narrative of loyalty to the Confederacy. The monument to “Union County’s Confederate Pensioners of Color,” dedicated by the Sons of Confederate Veterans in 2012 to support the loyal slave narrative crafted by former Confederates and proponents of the Lost Cause, best exemplifies later extensions of ex-Confederates’ efforts to create a physical landscape that reflected what Confederate sympathizers saw as the ultimate rectitude of the Confederate cause. In the wake of national reckoning with Confederate sentiment, the state has begun to reevaluate its heritage in recent years, and more emphasis now falls upon the many Union sympathizers who called North Carolina home in the 1860s. Perhaps the best depiction of this reckoning is 2021’s memorial to the United States Colored Troops, entitled “Boundless,” which features several ranks of soldiers following a color bearer who are marching towards the remnants of Confederate earthworks in Wilmington, marching towards the future – not only the end of the war, but the years of struggles and setbacks that followed. Yet, that flag held aloft symbolizes just what it did for so many black North Carolinians who flocked to Union lines during the war – freedom and hope for a better tomorrow.

Slavery divided North Carolinians from the colonial period to Reconstruction. Suspected by their fellow Confederate states of harboring loyalty to the Union, particularly considering the state’s substantial desertion rate, North Carolinians remained divided during the Civil War. After the war concluded and the Confederacy dissolved, former Confederates easily assumed control of the state government. Attempting to avenge their honor and wash away the accusations of disloyalty hurled at them during the war, these men launched an offensive to assert their devotion to the former Confederacy in all aspects of public life. By day, these men passed legislation to support white supremacy, disenfranchise black men, and achieve the construction of a new society that closely mirrored the Antebellum political and social order. The Confederate monuments they erected dominated the landscape – a visible depiction meant to reinforce the accepted view of the Civil War. By night, many of these same men terrorized Union sympathizers, United States Colored Troops veterans, formerly enslaved people, and anyone who dared question their authority. Their violent campaign across the state could not be stopped, even by men like Wyatt Outlaw, George W. Kirk, and the state’s own governor, William W. Holden. Yet, even during the terrifying turbulence of the postwar years, North Carolinians hardly held monolithic views on the Confederacy and its legacies; significant pockets of long-devoted Unionists and their descendants fought their own civil wars with die-hard former Confederates as they attempted to correct the historical record with their own string of monuments to adorn the commemorative landscapes of the war. But, it was only decades later in the 1940s, amidst the upheaval of World War II and the rise of the civil rights movement, did the state’s atmosphere begin to shift. Although the state refused to abandon its romanticization of the Confederacy during the Civil War Centennial, the election of nineteen black legislators to the state’s General Assembly in 1989 represented a marked improvement, and Unionist monumentation emerged into more public spaces. However, myriad organizations and individuals continued to erect more Confederate monuments, still clinging to the state’s idealized past. The state’s Union monuments remain outnumbered by its Confederate monuments, though modern monuments, like the “Boundless” memorial to the United States Colored Troops, have begun to recognize the lesser-discussed aspects of the state’s history and provide a more nuanced alternative to the dominant pro-Confederate discourse. Nonetheless, it cannot be forgotten that just twelve years ago, the Sons of Confederate Veterans dedicated a “loyal slave” monument in Union County. Today, much as one hundred years ago, North Carolina remains haunted by the memories of its Confederate past.

Table 1: Data Sources

| Name | Creator | Date Valid For | Description | Hyperlink |

| North Carolina Counties | T.I.G.E.R. | 2023 | Shapefile representing North Carolina counties. | Link |

| Whose Heritage Master Sheet | Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) | 2024 | Google sheets dataset containing name, location, date of dedication, and other available information of all Confederate monuments across the United States. | Link |

Works Referenced

Alexander, Roberta Sue. “Convention of 1865.” NCPedia. Accessed September 17, 2023. https://www.ncpedia.org/government/convention-1865#:~:text=The%20constitutional%20convention%20also%20resolved,transition%20from%20slavery%20to%20freedom.

The American Presidency Project, University of California – Santa Barbara. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/statistics/elections/1860.

Barrett, John G. The Civil War in North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1963.

Carbone, John S. The Civil War in Coastal North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Census of Agriculture Historical Archive. “1850 North Carolina Census of Agriculture.” https://agcensus.library.cornell.edu/wp-content/uploads/1850a-13.pdf.

“Chattel Slavery in the Appalachians of North Carolina.” Carl Sandburg Home National History Site. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/chattel-slavery-in-the-appalachians-of-north-carolina.htm.

Larson, Norman C. “The North Carolina Confederate Centennial Commission.” The North Carolina Historical Review 38, no. 2 (April 1961): 194-198. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/23517215.pdf.

Leloudis, James L., and Robert R. Korstad. Fragile Democracy: The Struggle Over

Race and Voting Rights in North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

NCPedia. “Black Codes in North Carolina, 1866.” https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/primary-source-black-codes.

NCPedia. “The Growth of Slavery in North Carolina.” https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/growth-slavery-north.

United States Civil War Centennial Commission. The Civil War Centennial: A Report to the Congress. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1968. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Civil_War_Centennial_a_Report_to_the/XB93AAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.