By Ziv Carmi ’23

Historical Context

When thinking of southern states that played a central role in the Civil War, Mississippi undoubtedly stands out. The home state of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Mississippi was the second to secede from the Union, following South Carolina (Marszalek and Williams 2009). Indeed, at the time of secession, Mississippi’s enslaved population outnumbered the white demographic by 83,000 (Marszalek and Williams 2009).

Strategically bounded to its west and south by the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico, respectively, Mississippi was the site of several notable military engagements. Indeed, the 1862 siege and Battle of Corinth and 1863 Battle of Jackson proved vital to ensuring Union successes in the Western Theatre. Most notably, however, Mississippi played host to “the turning point in the West,” in July 1863, with a Union victory at Vicksburg ensuring the permanent, debilitating bisection of the Confederacy. This event was so reviled by Mississippians that the city of Vicksburg refused to celebrate the 4th of July (the day Vicksburg fell) for about 80 years (Seratt 2017). In February of 1864, General Sherman and his troops famously destroyed the infrastructure within and around the east-central city of Meridian, including a Confederate arsenal, military hospital, POW stockade, several state offices, and the railroads leading to and from the city; following this event, Sherman allegedly said that “Meridian no longer exists” (City of Meridian). While many military historians focus on the movements of Union troops across Mississippi, the story of Jones County is just as notable. Near the end of the war, approximately 125 locals from the southeastern portion of the state, led by Newt Knight, rose up against the Confederacy and hoisted the American flag over the courthouse in Ellisville (Kelly 2009). While it is still unclear whether Jones County officially seceded, Sherman received a declaration of independence from Knight and his men in February 1864 and, briefly, the pro-Confederate government was ousted (Kelly 2009).

Despite Mississippi’s key roles in the Civil War, Mississippians constituted one of the smaller demographics within the Confederate army. Indeed, of the 750,000 to 1.228 million men whom the National Park Service estimates served in that army, only about 80,000 of them were white men from Mississippi (Marszalek and Williams 2009). Although there are few complete or reliable records of the exact numbers, we do know that slaves from numerous Confederate states were forced into manual labor in the trenches and in the camps of Civil War battlefields, so it is likely that many enslaved Mississippians also served in this capacity, but never as armed combatants. Indeed, even after the Confederate Congress legislated, in March 1865, that slaves could legally fight in Confederate armies the state adamantly opposed giving black men weapons (Marszalek and Williams 2009). Following the end of the war, Mississippi, despite sending the first black man to serve in the US Senate, passed the first and harshest Black Codes, designed to minimize the rights and freedoms for newly emancipated people (Phillips 2006). Despite the promise of equality from Radical Republicans, the Klan and other white supremacist groups committed several egregious acts of violence around the state, resulting in an environment thick with political intimidation and fear (Phillips 2006).

The Confederacy has also figured prominently in Mississippi’s state identity and culture since Reconstruction. Beauvoir, Jefferson Davis’s post-war estate in Biloxi, became one of the most famous homes for Confederate veterans following Davis’s death. Indeed, until June of 2020, the flag of Mississippi bore the Confederate Cross in its canton; it was the last state in the country to feature Confederate iconography in its flag.

One of Mississippi’s more noted figures was William Faulkner, an Oxford, Mississippi writer whose works often evoked the memory of the Confederacy. One of the most iconic images Faulkner repeatedly recalled in his literary works is that of the monument to the common Confederate soldier standing in the local town square, which speaks to the enormous weight that the Confederacy carried in the collective consciousness of the state through the 20th century. While Faulkner’s stories were set in fictional Yoknapatawpha County, they were very much based on his upbringing and experiences in Mississippi, illuminating how the “Old South” lived on, even hauntingly, in the minds of Mississippians generations after the war.

During the Civil Rights era of the mid-twentieth century, the state witnessed some of the most radical and defiant episodes of racial violence and stringent segregation, resulting in infamous incidents such as the brutal 1955 murder of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till by white supremacists (who were ultimately acquitted of the crime) and the 1962 race riot at Ole Miss after James Meredith became the first black student to enroll at that institution. Despite the dangers, black Mississippians such as Meredith continued to protest and fight for civil rights through events such as the 1961 Freedom Rides, the 1964 “Freedom Summer,” and various other efforts spearheaded by the NAACP, SNCC, and CORE.

Given Mississippi’s uniquely entangled relationship with its Confederate past, the state poses numerous fascinating questions about the nature of the Confederate monumentation therein. Those advocating for the removal of Confederate monuments argue two main points: First, these monuments were erected to protect white supremacy and prop up Jim Crow laws in the face of calls for racial equality and the long Civil Rights movement, and second, they honor men who committed treason against the United States, such as Robert E. Lee or Jefferson Davis.

The objective of this report is to examine the basis for these arguments using maps and historical sources. The aim is not to unequivocally answer these controversial questions or make any argument in support or against the monuments, but rather to provide concrete data and historical context to the debate. The first goal of this report is to map when, where, and by whom Confederate monuments were erected in Mississippi from the Reconstruction era to the present (spring 2021). The second goal of this study is to understand exactly how common monuments to specific individuals are in Mississippi. This study focuses solely on monuments, memorials, and statuary, and omits buildings, roads, or natural features named after Confederate soldiers or statesmen.

Results

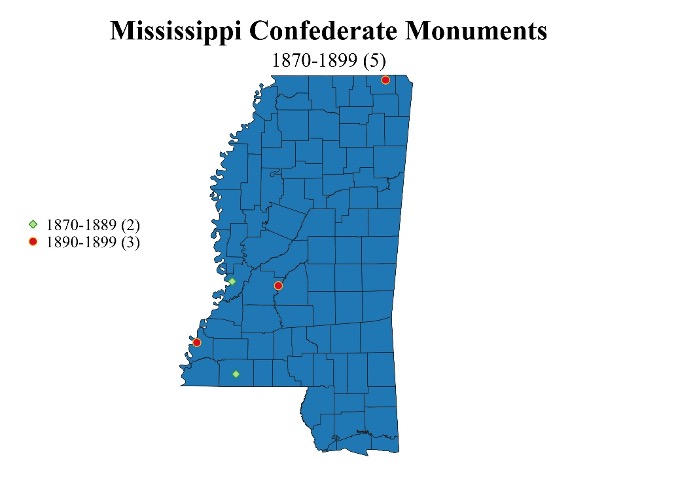

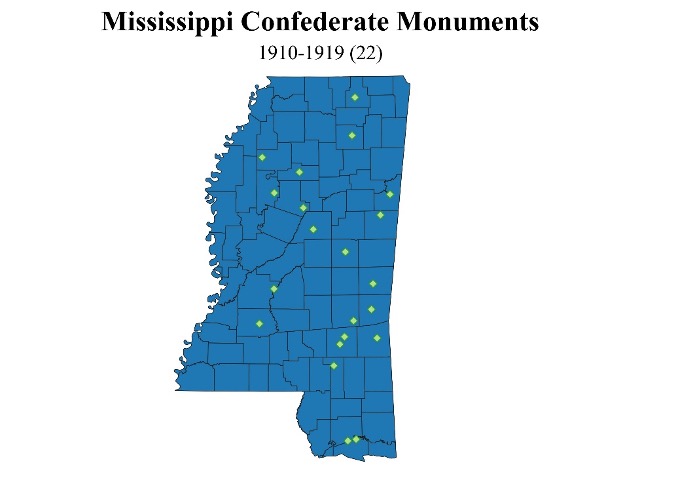

As is true of most other southern states, an overwhelming majority of Confederate monuments in the state of Mississippi are dedicated to non-specific honorees. Of the 52 statues erected, 46 of them (88.46%) have no specific honoree (Map 1). While three monuments do not have any recorded date of erection, it is evident that most statues were erected between 1900 and 1919. Of the 49 statues with recorded dates, 40 of them (81.63%) were erected in this time period (Maps 3 and 4). The geographic spread of the monuments put up during this period is intriguing. For the first decade of monumentation, statues were mainly built in the northern and western regions of Mississippi (with no statues erected in the southeast part of the state), whereas, in the second decade, statues were erected across a notably wider geographic scope, including the eastern and southern portions of the state, and nearly neglecting the western sectors.

Most of these statues were dedicated between 1910 and 1913, with no new statues erected between 1914 and 1917. However, interestingly enough, three statues were built following America’s entry into the First World War.

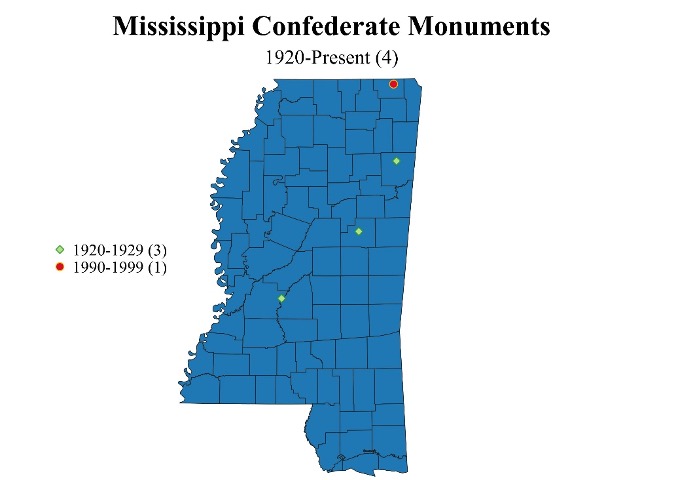

The erection of new monuments almost completely ceased in the 1920s, with only three new statues constructed in 1921, 1924, and 1926, respectively (Map 5). Interestingly, no new Confederate monuments were built until 1992, when the Corinth Confederate Memorial was established.

Analysis Results

Much of the debate surrounding Confederate monuments in general tends to focus on whom these statues are memorializing. Arguments center around the ethics and value of honoring men such as Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, and Stonewall Jackson, who committed treason against the US as they tried to form a nation built upon slavery and white supremacy.

While, of course, several statues do honor specific people, nearly 90% of the Confederate statues in Mississippi are dedicated to non-specific honorees. It is curious that, of the monuments that are dedicated to individual Confederates, not a single one is devoted to Robert E. Lee; although Lee is often regarded as the Confederate hero of the eastern theater, which Mississippi lay outside of, one would think there might be at least one statue recognizing his importance to the entire Confederacy . However, as expected, a majority of these monuments memorialize Jefferson Davis, with three dedicated in his name and one in his wife Varina’s name. Unexplainably, though, the three monuments to Davis are all highway markers, indicating that Mississippians declined to erect actual statues in their native son’s image. The other two honorees include Nathan Bedford Forrest and Colonel William P. Rogers. Forrest, the infamous Grand Wizard of the Klan, was responsible for several victories (and a defeat at Tupelo) in his 1864 defense of the northern part of the state; however, this monument is located in Forrest County, which is in southern Mississippi. This geographic nonconformity poses an interesting question as to why Forrest County decided to name itself in the cavalry commander’s honor, as it appears he did not fight in that region at all. Even more quizzically, Rogers was actually a Texan, (who incidentally, served under Davis during the Mexican-American War) who led several disastrous charges at Corinth, located in extreme northeastern Mississippi, before being struck by several bullets and immediately killed. Rogers’s regiment, the Second Texas Infantry, lost more than half its men, and their failure contributed significantly to the Confederacy’s loss of that battle. Apparently, despite his unfruitful military efforts, Rogers’s actions were considered heroic, with his bravery worthy of memorialization in the eyes of Corinth’s residents. Like several other icons revered in the Lost Cause mythology, it appears that Rogers’s martyrdom made him an alluring figure to remember the “Old South” by.

The motivations behind other Confederate monuments within the state are more curious. In particular, the two monuments in Jones County, the rebellion site of Newt Knight and his company, raise several questions. Indeed, the United Daughters of the Confederacy actually erected a monument in 1912 on the grounds of the infamous Ellisville courthouse where Knight’s men raised the American flag in rebellion against the Confederate Government. What is even more curious about this monument is that was dedicated during Knight’s lifetime (Kelly 2009). However, by this point in time, Knight, who lived on a farm in nearby Jasper County, had become a controversial figure due to his support of Civil Rights and the Republican Party, and due to his marriage to a formerly enslaved woman. That the UDC chose to erect a monument at this specific location during the course of Knight’s life appears to be a clear rebuke of his disloyalty to the Confederate cause and an attempt (per the Lost Cause narrative) to mask the numerous internal divisions and dissent that plagued pockets of the South throughout the Civil War.

The numerical and geographic scope of Mississippi’s Confederate monuments is also intriguing. Indeed, the entry for the Jones County Courthouse in the National Register of Historic Places notes that Confederate monuments “though widespread, are not as ubiquitous as is sometimes thought” (National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1994). The entry also notes that many of the monuments, especially most of the older ones dating before 1900, are located in cemeteries rather than outside courthouses (National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1994). This trend likely reflects a changing cultural attitude toward Confederate monuments within the state; while it appears that these monuments were initially intended primarily to honor the dead, around the turn of the century, the monuments adopted a broader meaning. This phenomenon also happens to coincide with the surge of monumentation across the South as a whole and the resurgence of Southern nationalism.

The dedication date of the Ellisville Courthouse statue is fairly consistent with that of other Confederate monuments across the state. Indeed, most Mississippi courthouse statues were erected between 1900 and 1917; by 1994, statues stood at approximately 27 of the 92 active Mississippi county court buildings, and three stood at former courthouse locations (National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1994). Of the 52 monuments erected across the state, a sizable portion (30 making for about 57.7% of all statues in Mississippi) stood outside courthouses (or, in the case of some aforementioned monuments, former courthouses), further indicating a popular embrace of a broader cultural meaning behind these statues than the late 19th-century purpose of merely mourning or honoring the dead. In other words, in the early 20th century, honoring the Confederate dead via sculpture became more of a civic, and perhaps more politicized, ritual than ever before. Since veterans began passing away in large numbers during this period, it is possible that this tradition of statuary arose as an alternative way to keep the memory of the war alive.

Another reason for the shift to courthouse monumentation might be explained as a response to the evolving racial ideas of the Progressive Era. Despite the landmark 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson upholding segregation, Progressive Era politicians such as Teddy Roosevelt were relatively liberal regarding racial relations, something that likely alarmed many white Mississippians who supported Jim Crow. Indeed, several major advancements in racial equality were made during this period. Two such events were the formation of the NAACP in 1909, and, in 1901, the invitation of Booker T. Washington, to dine with the President (the first black man invited to dinner in the White House). The latter event, in particular, raised much fury from Southerners; James Vardaman, a notorious white supremacist who would later be elected governor and Senator by Mississippians, said that the White House was “so saturated with the odor of the [n*****] that the rats have taken refuge in the stable” (Gatewood 1984, 433). Given Vardaman’s popularity within the state’s white demographic, it is reasonable to assume that perhaps the resurgence of monumentation during this period occurred as a backlash to the initial attempts at racial equality or a way of bolstering segregationist policy that arose during this period. Indeed, it is quite possible that, as governor from 1904 to 1908, Vardaman himself encouraged monumentation throughout the state as a way to garner support for his policies.

However, despite the prevalence of statues located at courthouses compared to other locations, only about 43 county seats (fewer than half) in the state have prominent public memorials to the Confederacy outside of cemeteries (National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, 1994). Given how county seats often serve as the more populated and more historically cognizant centers of their respective areas, this pattern raises some questions about the pattern of Confederate monumentation, or lack thereof, within the state. Since white Mississippians clearly cherished their Confederate past and Southern nationalism in the late 19th- and early 20th century (as evidenced by the 1894 adoption of a flag with strong Confederate symbolism), it is odd that monumentation—particularly near county courthouses—dropped off so dramatically by the 1920s. More research must be done to assess whether a possible lack of finances chiefly was responsible for the lack of monumentation in certain areas or if different cultural or political factors contributed to the dearth of memorials.

As noted above, following 1926, the construction of Confederate monuments totally ceased, with the exception of the lone 1992 monument at Corinth. Georgia’s monumentation in the 1920 similarly slowed down, so it is possible that this time period produced increased financial hardship for several Deep South. Indeed, since the UDC was largely responsible for sponsoring monuments in both states (37 of the monuments erected in Mississippi- over 70% of monuments statewide- were sponsored by the UDC), their local chapters or the state division might have fallen on hard times during the mid to late 1920s, explaining the cessation of monuments during that period. It is also strange that, unlike in many other southern states, Mississippi erected no monuments during or around the Civil War Centennial in the 1960s or in response to the mid-20th century Civil Rights movement. Although Confederate monuments are, by no means, always or predominantly erected in response to white racial attitudes of the time, it is curious, given Mississippi’s especially deep and long-fraught battles over race relations, that the state did not turn to monumentation during this time as a means to reinforce many Mississippians’ commitments to white supremacy in the face of calls for black civil rights. It is also curious that no monuments were erected in the state around the 125th anniversary of the war (although the Corinth memorial was erected in 1992 two years after the 125th anniversary ended, suggesting that perhaps the monument was planned for the anniversary but delayed, possibly due to a lack of funds) or the Civil War Sesquicentennial, which saw small flurries of monumentation elsewhere. Given the state’s strong Confederate and southern nationalist pride, this phenomenon is baffling. While financial reasons may have played a significant role, further research is required to determine the exact reasons for Mississippi’s abrupt halt to monumentation after the 1920s.

Conclusion

Confederate monuments in the state of Mississippi provide several fascinating and unique insights into the forging of historical memory in the post-war South. They are overwhelmingly dedicated to the common Confederate soldier rather than specific individuals. Indeed, both a chronological and geographic examination of which monuments were erected when and where raises many questions, such as why the southeast region of the state did not erect monuments sooner and what caused of the cessation of monumentation in the late 1920s.

While the arguments put forth by individuals on both sides of the Confederate monument debate have merits, many of them overlook the complexities and nuances of Confederate monuments when analyzed by specific location, genre, and origins, as this map and report does with Mississippi. Indeed, the specific context of these individual monuments, their dates of erection, their subject matter, and the full nature of their dedication speeches require reevaluation, or a more complete examination of the individual stories behind these monuments. As these maps show, the context surrounding Confederate monuments in the state of Mississippi is a lot more complex and multi-layered than strict proponents of either the “wholly white supremacy-inspired” or “wholly martial sacrifice-inspired” schools of thought have frequently made them out to be.

This research, of course, has its limitations. It does not map schools, buildings, towns, counties, roads, or natural features named after Confederates, all of which are extraordinarily prevalent throughout Mississippi. Additionally, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s data used to create these maps was generated through crowdsourced map points, and the exact locations cannot be immediately verified. Furthermore, several monuments do not have dates of dedication or erection, which limits a complete and thorough analysis of the data. Without a thorough examination of the full historical context of each and every monument’s story, such as dedication speeches and events, monument inscriptions, and symbology, final conclusions about the exact historical nature of Confederate monumentation in Mississippi leave many intriguing questions still unanswered. However, these maps and this report seeks to draw attention to the intricacies of monumentation patterns in Mississippi as well as highlight the importance of further research into some of these currently unanswerable questions.

Table 1: Data Sources

| Name | Creator | Date Valid For | Description | Hyperlink |

| Mississippi Counties | MARIS | 2019 | Shapefile representing Mississippi counties. | Link |

| Whose Heritage Master Sheet | Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) | 2019 | Google Sheets dataset containing name, location, date of dedication, and other available information of all Confederate monuments across the United States. | Link |

Works Referenced

“History.” City of Meridian.https://www.meridianms.org/residents/history/#:~:text=In%20February%201864%2C%20General%20William,the%20city%20continued%20to%20grow.

Cutrer, Thomas W. 2018. “Nathan Bedford Forrest.” Mississippi Encyclopedia. https://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/nathan-bedford-forrest/

Foster, Lisa C., and Susannah J. Ural. 2017. “Jefferson Davis Soldier Home- Beauvoir.” Mississippi HistoryNow. http://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/articles/411/jefferson-davis-soldier-home-beauvoir

Gatewood Jr., Willard B. 1984. “A Republican President and Democratic State Politics: Theodore Roosevelt in the Mississippi Primary of 1903.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 14, No.3: 428-436. https://www-jstor-org.ezpro.cc.gettysburg.edu/stable/pdf/27550103.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A160adb4771a3cdb2ded80bb3580adaf2

Kelly Jr., James R.2009. “Newton Knight and the Legend of the Free State of Jones.” Mississippi HistoryNow. http://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/articles/309/newton-knight-and-the-legend-of-the-free-state-of-jones

Marszalek, John F., and Clay Williams. 2009. “Mississippi Soldiers in the Civil War.” Mississippi HistoryNow. http://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/articles/175/mississippi-soldiers-in-the-civil-war

McGreevy, Nora. 2020. “Mississippi Voters Approve New Design to Replace Confederate-Themed State Flag.” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/mississippi-will-replace-its-confederate-themed-state-flag-180976209/

National Park Service, 2015. “The Civil War: Facts.” https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/facts.htm

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. 1994. “Jones County Courthouse and Confederate Monument at Ellisville.” https://www.apps.mdah.ms.gov/nom/prop/15415.pdf

Parrish, Michael T. 2017. “Rogers, William Peleg.” Handbook of Texas Online. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/rogers-william-peleg

Philips, Jason. 2006. “Reconstruction in Mississippi, 1865-1876.” Mississippi HistoryNow, http://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/articles/204/reconstruction-in-mississippi-1865-1876

Rucker, LaRecca. 2015. “Confederate Memorial in Faulkner’s Works.” The Oxford Eagle,https://www.oxfordeagle.com/2015/09/06/confederate-memorial-in-faulkners-works/

Seratt, Bill. 2017. “Celebrating Independence Day.” Visit Vicksburg. https://visitvicksburg.com/vicksburg-independence-day

Theodore Roosevelt Center. n.d. “Booker T. Washington.” https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Learn-About-TR/TR-Encyclopedia/Race%20Ethnicity%20and%20Gender/Booker%20T%20Washington

Theodore Roosevelt Center. n.d. “NAACP.” https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Learn-About-TR/TR-Encyclopedia/Race%20Ethnicity%20and%20Gender/NAACP

US Bureau of the Census. 1910. “Statistics for Mississippi.” https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1910/abstract/supplement-ms.pdf

US Bureau of the Census. 1920. “Mississippi.” https://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/06229686v20-25ch3.pdf

Winkleman, Roy. 2011. “A Monument to Colonel William P. Rogers.” ClipPix Etc. https://etc.usf.edu/clippix/picture/a-monument-to-colonel-william-p-rogers.html?refresh=359420343

Winkleman, Roy. 2011. “A Statue Depicting Colonel William P. Rogers.” ClipPix Etc. https://etc.usf.edu/clippix/picture/a-statue-depicting-colonel-william-p-rogers.html?refresh=597565803