By Ziv Carmi ’23

Introduction

Georgia played host to some of the most significant events in the Civil War and its aftermath. Seceding in January 1861, the state was one of the original seven to leave the Union prior to the shelling of Fort Sumter. It was a Georgian who presided over the convention of seceded states that February; it was a Georgian who primarily wrote the Confederate Constitution; and it was Georgians who held the positions of Vice President and Secretary of State. It was in Savannah on March 21, 1861, that Alexander Stephens, the Vice President of the new Confederacy, delivered his now-infamous speech in which he declared that “our new government is founded on exactly the opposite idea [of racial equality]; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition,” establishing a clear linkage between the Confederacy and white supremacy. Georgia is infamous for the massive amount of destruction it faced in the wake of Sherman’s marches through the state. And it was in Georgia where, shortly after the end of the war, a fugitive Jefferson Davis was arrested.

The Confederacy has loomed large in Georgia’s state identity and culture since the 1860s and 1870s. Until 2001, the Confederate battle flag remained a prominent part of the Georgia state flag, and even today, the Georgia flag still invokes the memory of the Confederate Stars and Bars.

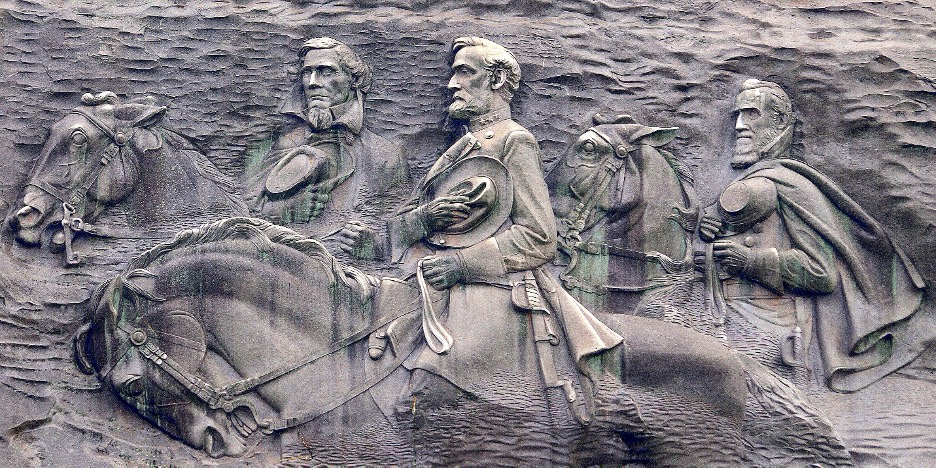

Stone Mountain, the largest Confederate monument and largest relief sculpture in the world, was built with state funds and completed in the 1970s. About 4 million visitors come to Stone Mountain Park each year (Boissoneault 2017). While debate swirls regarding the future of Confederate monuments in Georgia, a statute currently protects all plaques, monuments, and memorials dedicated to the veterans of the Confederacy (Boissoneault 2017). This law remains incredibly controversial today.

Those advocating for the removal of Confederate monuments argue two main points: First, these monuments were erected to protect white supremacy and prop up Jim Crow laws in the face of calls for racial equality and the long Civil Rights movement, and second, they honor men who committed treason against the United States, such as Robert E. Lee or Jefferson Davis.

The objective of this report is to examine the basis for these arguments using maps and historical sources. The aim is not to unequivocally answer these controversial questions or make any argument in support or against the monuments, but rather to provide concrete data and historical context to the debate. The first goal of this report is to map when and where Confederate monuments were erected in Georgia from the Reconstruction era to the present (winter 2020). The second goal of this study is to understand exactly how common monuments to specific individuals are in Georgia. This study focuses solely on monuments, memorials, and statuary, and omits buildings, roads, or natural features named after Confederate soldiers or statesmen.

Results

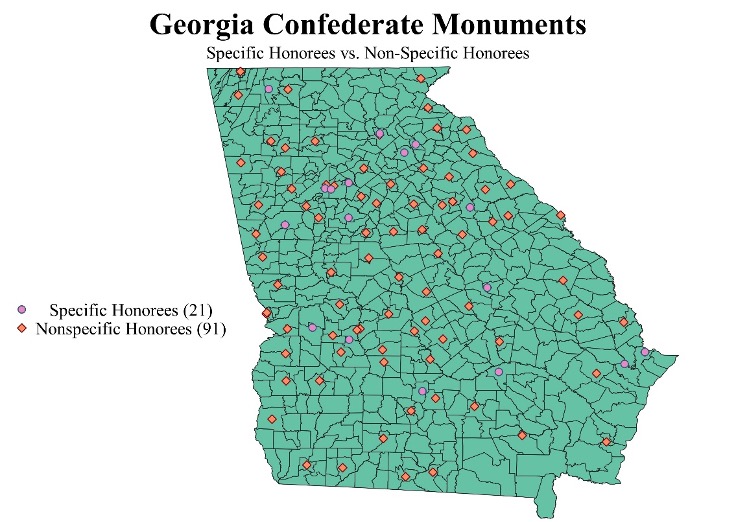

An overwhelming majority of Confederate monuments in the state of Georgia are dedicated to nonspecific honorees. Of the 112 statues in Georgia, 91 of them (81.25%) have no specific honoree (Map 1).

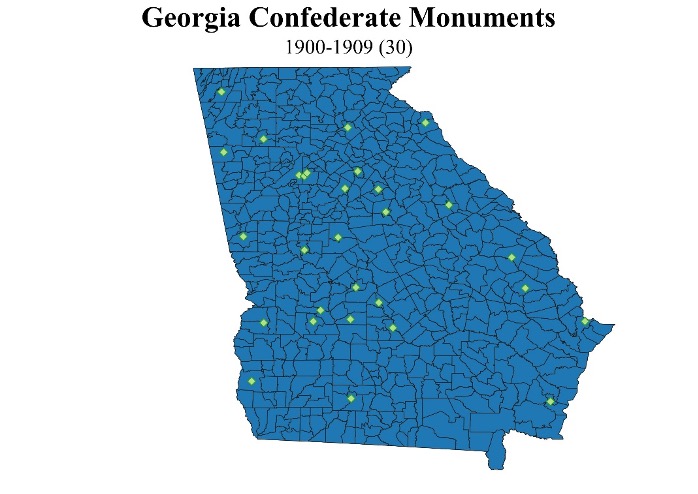

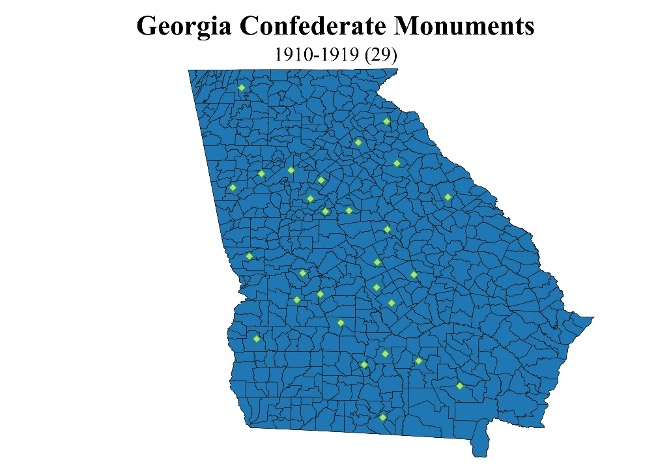

While fourteen monuments do not have any recorded date of erection, it is evident that most statues were erected between 1900 and 1919. Of the 98 statues with recorded dates, 59 of them (60.2%) were erected in this time period (Maps 3 and 4). While this fervent monumentation may, of course, be related to the resurgence of white supremacist policies that occurred during the era, it might also have arisen out of the state finally achieving enough financial stability, after the turbulence of the immediate postbellum years, to fuel monumentation efforts; financial changes, coupled with an aging and dying veteran population, undoubtedly contributed to the flurry of monumentation. There is no one explanation for why statues were erected; reading the full dedication speeches of each monument is key to understanding the motivations behind them. Indeed, for some statues, there were even multiple reasons described in separate dedication speeches, showing just how multifaceted the purposes behind these memorials were.

As America entered into World War I in 1917, statue-erection totally ceased, with no monuments created between 1917 and 1922. Monumentation efforts continued to remain relatively stagnant into the 1920s, with only five erected during the decade (Map 5).

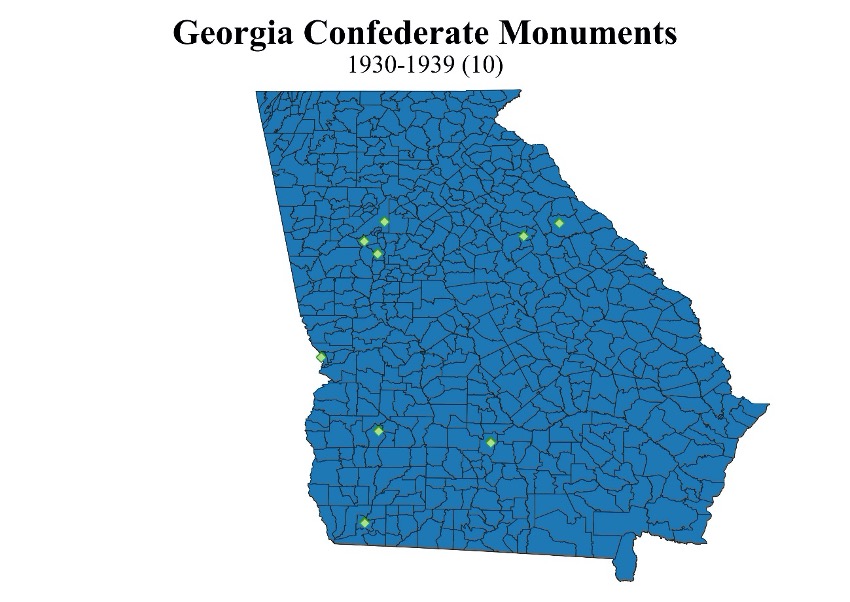

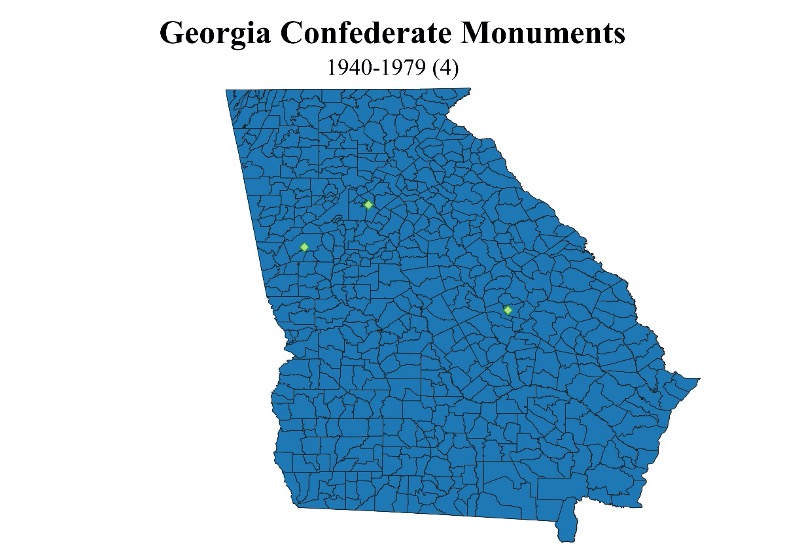

Following the onset of the Great Depression, however, more monuments went up, with ten erected between 1930 and 1939. Most of the statues of the 1930s were from the latter half of the decade, with eight of the ten either fully or co-sponsored by the UDC. Between 1940 and 1979, only four monuments were erected, and between 1990 and 2012, only five went up. No new Confederate monuments have been erected since 2012.

Of this latter set of monuments, Stone Mountain is a special case. While it was finished in 1972 and appears in our data as such, Gutzon Borglum (of Mt. Rushmore fame) was appointed as the sculptor in 1915. Due to many factors, such as World War I, lack of funds, and a change in sculptors from Borglum to Augustus Lukeman, the project was delayed for many years. It was not until 1964 that work on the mountain actually continued, funded by the state, which had bought the land in 1958. Since Stone Mountain has such a long history, it is reasonable to back-date the relief to its inception date in the 1910s, which also coincides with the height of monumentation in Georgia.

Much of the debate surrounding Confederate monuments in general tends to focus on who these statues are memorializing. Arguments center around the ethics and value of honoring men such as Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, J.E.B. Stuart, and Stonewall Jackson, who committed treason against the US as they tried to form a nation built upon slavery and white supremacy.

Analysis

While, of course, many statues do honor specific men, over 80% of the Confederate statues in Georgia are dedicated to nonspecific honorees. Of the ones that are dedicated to individual Confederates, only one is devoted solely to Robert E. Lee and one to Jackson and Stuart each, while six are devoted solely to Jefferson Davis. While two of these are highway markers, it appears that several of the other four are related to Davis’ flight and subsequent capture by Union forces in May 1865.

It is interesting to note, however, that blatantly missing from this group of individual honorees are several Georgia notables. For example, there are no monuments dedicated to native sons and Confederate architects Alexander Stephens or T.R.R. Cobb, who drafted the Confederate Constitution and died at Fredericksburg. There are also no statues devoted to the commanders who led forces in defense against Sherman, whose name, to this day, is vilified amongst portions of the state. Conversely, James Longstreet, who became a Republican and outspoken critic of Robert E. Lee, and thus was heavily criticized by southerners and diehard defenders of the Lost Cause, has a monument to himself. The inclusion of Longstreet and exclusion of the other figures, who could be considered heroes in the context of the Lost Cause myth, creates some interesting questions about the nature of memory, who society chooses to honor and why.

Many activists also argue that Confederate monuments were erected as a direct reaction to the attempts at racial equality that began during Reconstruction and the late 19th century, with a few specific monuments denoted as a reaction to the Civil Rights movement. Indeed, there is a strong association of Confederate monuments with the period of perpetuation of white supremacy and the Lost Cause at the turn of the century. The period between 1890 and 1920 saw a resurgence of racism with the 1896 Supreme Court ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1915 film Birth of a Nation, and the revival of the Klan. While, of course, correlation does not mean causation, there is evidence to indicate that some of these monuments were erected to further Lost Cause ideals. For example, Henry Wirz, the commandant of Andersonville who was convicted of war crimes, was framed as a martyr by the Lost Cause myth. A monument was erected in his honor in 1909 (National Park Service, 2020).

Furthermore, 71 of the monuments erected in Georgia were sponsored by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. 49 of those were erected in the late 1890s, the 1900s, and the 1910s. From the period of 1890-1919, only 64 monuments total were erected, which means that over 80% of those dedicated during this period were sponsored by the UDC. According to some scholars such as Karen Cox, the UDC went beyond pure memorialization and actively promoted the Lost Cause and Southern vindication (Campbell 2004). In fact, in 1903, the UDC endorsed a primer titled “The Ku Klux Klan or Invisible Empire” and encouraged its use in schools (Campbell 2004). Due to the nature of the UDC, it is reasonable to suspect strong linkages between monumentation and white supremacy.

However, another very likely reason driving the rampant monumentation of this period is the enormous staying power of Georgians’ sustained mourning for the war-dead. The 1910s marked the fiftieth anniversary of the war, which resulted in a resurgence of statuary. Indeed, 58.6% of statues erected within the decade were dedicated during the semicentennial (1911-1915) when the memories of Georgia’s fallen sons likely loomed especially large. The South as a whole amassed heavy casualties during the war. Indeed, they lost a greater proportion of their men than Germany did during WWI, resulting in a heavy pall that centered much of southern historical memory around remembering and commemorating this huge loss. For families who were unable to recover the bodies of loved ones from the battlefields, these more local monuments within their state served as physical reminders of their family’s and community’s sacrifices and provided communal spaces in which to grieve and to heal. Indeed, this is likely why monuments in Georgia are overwhelmingly dedicated to the common Confederate soldier rather than to specific Confederate honorees. Some scholars have explored this phenomenon, concluding that the large amounts of Confederate monuments in the early 20th century was associated with the fears that memories of the “old” antebellum South and Confederacy, as well as of individual human sacrifice, would be lost with the passing of Confederate veterans, who were dying off at a large rate around this time (Cox 2003).

Financial reasons also likely were a factor in the timing of monumentation surges and “droughts” in Georgia. In the immediate postbellum era, southern states’ financial coffers were close to empty; it was not until at least ten years after the conflict that southerners’ financial fortunes had bounced back enough to fund the creation of Confederate monuments, which coincides with the first “surge” of five monuments in 1878-79 (This, of course, also occurred during the “Redemption” and Jim Crow years). In the case of Stone Mountain, the delay between the monument’s inception in 1915 and its finalization in 1972 was indeed due in large part to a lack of funds, as well as other non-race-related issues. Additionally, of the five monuments dedicated during the 1920s, a critical gap occurred between the flurry of monumentation in the 1910s and the relative surge of monuments in 1922-1923. This gap was likely due to a lack of funds and manpower thanks to American participation in WWI, while the sharp uptick of completed monuments three to four years after the armistice was likely due to the financial boom following the war. That only one monument was erected between 1923 and 1934 following the 1922-23 surge is a curious phenomenon and requires closer analysis to determine causation.

The fact that any monuments were erected during the Great Depression, which hit southern states especially hard, is also financially puzzling, but may speak to Georgians’ appeals to the sacrifice and suffering of their ancestral Civil War soldiers to help inspire fellow Georgians to muster similar strength in order to endure the hardships of the Depression era. The fact that two of the 1930s monuments were sponsored by the Works Progress Administration supports the notion that even the Federal government considered the creation of Civil War monuments—even those honoring the Confederacy—as a means to both help fuel the economy and stoke a renewed commitment to stoic sacrifice and patriotism in the immediate post-Depression years. The rise in monumentation during the late 1930s appears to correlate to the significantly improved financial fortunes of the South by the end of that decade, particularly amongst southern heritage groups such as the UDC, who either fully or co-sponsored eight of the ten monuments erected during the late 1930s.

As the decade turned and the years went on, monumentation slowed significantly, which seems to suggest a sinking interest in new monuments—a phenomenon which would be only natural with the receding memory of the war from the collective consciousness.

Conclusion

Confederate monuments in the state of Georgia provide fascinating insights into the forging of historical memory in the post-war South. They are overwhelmingly dedicated to the common Confederate soldier rather than specific individuals, but the individual honorees are curiously represented.

While the arguments used by individuals on both sides of the Confederate monument debate have merits, many of them overlook the complexities and nuances of Confederate monuments when analyzed by specific location, genre, and origins, as this map and report does with Georgia. Indeed, the specific context of these individual monuments, their dates of erection, their subject matter, and the full nature of their dedication speeches require reevaluation, or a more complete examination of the individual stories behind these monuments. As the maps show, the context surrounding Confederate monuments in Georgia is a lot more complex and multi-layered than strict proponents of either the “wholly white supremacy-inspired” or “wholly martial sacrifice-inspired” schools of thought have frequently made them out to be.

This research, of course, has its limitations. It does not map schools, buildings, towns, counties, roads, or natural features named after Confederates. Additionally, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s data used to create these maps was generated through crowdsourced map points, and the exact locations cannot be immediately verified. Furthermore, several monuments do not have dates of dedication or erection, which limits a complete and thorough analysis of the data. Additionally, this research is also limited in the geographic and cartographic nature of this study. However, although more work must be done to conduct a thorough examination of the full historical context of each and every monument or Confederate namesake—including full analyses of all dedication speeches and their associated commemorative events, monument inscriptions, and symbology—hopefully this state map, and State of the Confederacy project as a whole, will help shed light and provide useful nuanced perspectives on this controversial, but important historical subject.

Data Sources

| Name | Creator | Date Valid For | Description | Hyperlink |

| Georgia Counties | T.I.G.E.R. | 2019 | Shapefile representing Georgia’s counties. | Link |

| Whose Heritage Master Sheet | Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) | 2019 | Google Sheets dataset containing name, location, date of dedication, and other available information of all Confederate monuments across the United States. | Link |

Works Referenced

American Battlefield Trust. “John Bell Hood.” https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/john-bell-hood

Boissoneault, L. 2017. “What Will Happen to Stone Mountain, America’s Largest Confederate Memorial?” Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-will-happen-stone-mountain-americas-largest-confederate-memorial-180964588/

Bragg, W.H. 2005. “Reconstruction in Georgia.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/reconstruction-georgia

Campbell, J. 2004. “Campbell on Cox, ‘Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture.’” https://networks.h-net.org/node/2295/reviews/2395/campbell-cox-dixies-daughters-united-daughters-confederacy-and

Cox. K. 2003. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, Florida, USA.

Fowler, J. 2010. “Civil War in Georgia: Overview.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/civil-war-georgia-overview

Masur, L. 2011. The Civil War: A Concise History. Oxford University Press, New York, New York, USA.

National Park Service. 2015. “Joseph Wheeler.” https://www.nps.gov/people/joseph-wheeler.htm

National Park Service. 2020. “Captain Henry Wirz.” https://www.nps.gov/ande/learn/historyculture/captain_henry_wirz.htm

Stone Mountain Park. “Memorial Carving.” https://www.stonemountainpark.com/Activities/History-Nature/Confederate-Memorial-Carving

Tuck, S. 2004. “Civil Rights Movement.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/civil-rights-movement