By Isaac Shoop ’21

Historical Context

Home to the first capital of the Confederate States of America, Alabama is intimately tied to the history of the Confederacy. On January 11, 1861, Alabama became the fourth southern state to secede from the Union. On February 18, 1861, the newly formed Confederate States of America inaugurated Jefferson Davis as their first president on Alabama’s state house grounds in Montgomery, which served as the capital of the Confederacy until May, 1861 (Alabama Department of Archives and History).

The Confederacy has had a large imprint on Alabama’s history and culture since the end of the Civil War. The state flag of Alabama, a red St. Andrews cross atop a plain white field, invokes images of the Confederate battle flag, which also bears the cross (Alabama Department of Archives and History, 2014). The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which had a strong presence in postbellum Alabama, also links Alabama’s history and culture to the Confederacy. The KKK had been formed by Confederate veterans following the Civil War in an attempt to suppress the rights and freedoms former slaves received after the war. In the postwar years, the KKK flourished until 1870. At the beginning of the 20th century, the KKK resurged not just in Alabama, but throughout the entire country. In the 1920s, Alabama reportedly had 150,000 Klan members, while the KKK boasted 2.5 million members nationwide. In Alabama, Klansmen named their chapters after prominent Confederate leaders to showcase a direct link to their Confederate heritage (Feldman, 1999).

In response to the pernicious hold that white supremacy maintained in the former Confederate state throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Alabama played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The activist work of Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 became some of the most defining moments of the Civil Rights Movement. The freedom rides, “Bloody Sunday,” and Martin Luther King’s famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail” all took place in Alabama. All of these events aimed to dismantle the institution of segregation, which was a direct legacy of Alabama’s Confederate history.

The state also boasts numerous monuments, sculptures, and plaques to Confederate icons. In 2017, in the wake of multiple white supremacist-driven murders in South Carolina, Virginia and elsewhere, and the ensuing calls for the removal of Confederate iconography, the Alabama state legislature passed the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act which prohibits the “relocation, removal, alteration, renaming, or other disturbances” of monuments and related memorials that have been in place for 40 years or more (Alabama Historical Commission). This law protects a majority of Alabama’s Confederate monuments, as most were erected in the first half of the 20th century. As might be expected, the law has come under intense scrutiny in recent years and subject to litigation numerous times.

Over the past several years, calls for the removal of Confederate monuments across the country have grown stronger and gained increased support. While many monuments have been taken down across the South, many more are still standing. Those that seek the removal of Confederate monuments argue that the monuments glorify the Confederacy, a country founded upon slavery, and thus believe these monuments represent and perpetuate white supremacy. Those opposing removal argue that Confederate monuments do not represent or glorify white supremacy, but rather celebrate southern heritage and martial valor. Still others take a more nuanced position and acknowledge the multiple meanings and varying contexts of different monuments, but argue that the interpretive and educational value of the monuments should take center stage in the debates.

This report does not claim to be the final word on the Confederate monument debate, nor does it argue for or against the removal of Confederate statuary. It does, however, provide the reader with concrete data, presented through a series of maps, as well as historical context for the maps, to add nuance to the debate surrounding Confederate monuments in Alabama. First, this report maps when and where Confederate monuments were erected in Alabama from the turn of the 19th century to the present day. Secondly, this report maps which monuments are dedicated to specific individuals versus non-specific individuals in Alabama. This study only focuses on statuary and memorials; it does not include roads, schools, or buildings named after Confederate leaders.

Results

Of Alabama’s 57 total Confederate monuments, only nine of them are dedicated to a specific honoree. The other 48 monuments in Alabama have no specific honoree (Map 1). It is clear from this data that a majority of these monuments were erected between 1890 and 1919.

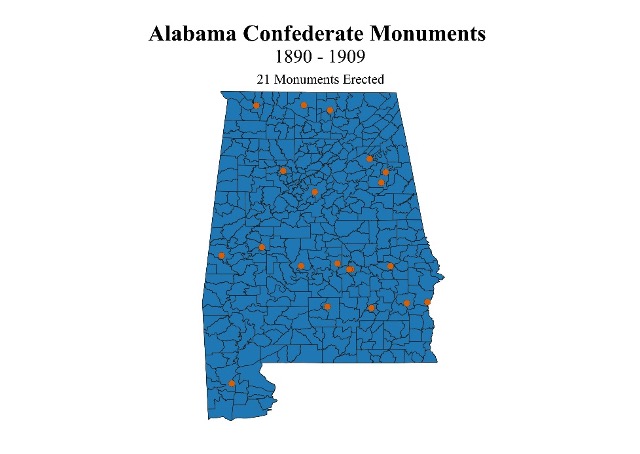

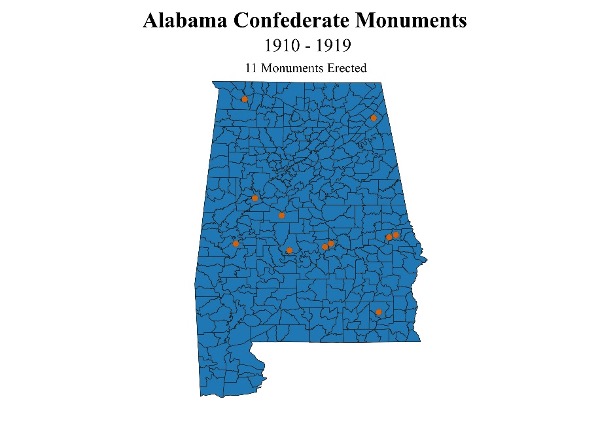

One monument did not have a recorded date of erection, but for the 56 monuments that did, 32 of them were erected between 1890 and 1919 (Maps 2 and 3).

Alabama never again experienced the same flurry of monumentation as it did from 1890 to 1919, but the state continued to sporadically erect monuments honoring the Confederacy throughout the 20th century. From 1920 to 1939, 11 monuments were erected (Map 4).

Following the 1930s, however monument building all but ceased in Alabama. From 1940 to 1989, there were only six monuments erected (Map 5). During the 1950s and 1970s, zero monuments were erected, while the 1960s only saw one new monument added. Three were erected in the 1940s, with two in the 1980s.

From 1990 to 2010, there have been seven monuments erected (Map 6). No Confederate monuments have been erected in Alabama since 2010.

Analysis of Results

The Confederate statues that incite the greatest debate are those that honor specific Confederate leaders, such as Robert E. Lee or Jefferson Davis. In Alabama, however, only nine of the 57 total monuments are devoted to such specific persons. Jefferson Davis and Nathan Bedford Forrest each have two monuments, while Joseph Wheeler, Robert E. Lee, Raphael Semmes, John Pelham, and John Tyler Morgan each have one monument dedicated to them. Jefferson Davis, Nathan Bedford Forrest, and Robert E. Lee are common figures who are memorialized throughout the South. The four other figures either were born in Alabama or lived in Alabama after the war. General Joseph Wheeler, Confederate Naval Captain Raphael Semmes, and General John Tyler Morgan all lived in Alabama after the war, while General John Pelham was born in Alexandria, AL. Given that most of Alabama’s monuments were erected from 1890 to 1919, one might expect to see more monuments dedicated to specific individuals such as these, given the popularity of the Lost Cause that idolized specific southern generals and politicians during this period. However, a majority of monuments in Alabama, 48, are dedicated to the common soldiers of the Confederacy.

There are many possible reasons for why the 1890-1919 time period saw a flurry of monumentation. This era marks the height of Jim Crow, when white supremacist ideologies and laws fueled a renewed interest in celebrations of the South’s Confederate past. However, this increase in monumentation also could be the result of a return to greater financial stability within the state after the tumultuous post-war years (Mauldin, 2017). Economic capacity, combined with a desire shared by many southerners to memorialize their rapidly aging and dying Confederate veterans likely played a role in the mass monumentation of the time period. However, one must look at these monuments on a case by case basis to truly understand why they were erected. Erected at different times, in different places, and by different sponsors, these monuments defy simplistic or monolithic classification.

As mentioned earlier, many individuals who support the removal of Confederate monuments argue that they were erected to support and maintain white supremacy throughout the South, in direct opposition to the calls for equality and civil rights. This argument has merit and must be taken seriously when considering these monuments, as the celebration and preservation of white supremacy certainly were key factors in the erection of numerous monuments. The resurgence of the KKK, the considerable sway of the Lost Cause, the rise of Jim Crow and segregation, and a mounting pressure to defend the actions of Confederate ancestors defined much of southern society during the 1890-1919 time period, when 32 of Alabama’s 57 monuments were erected.

It is important to note that the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) were key players in the memorialization efforts of this time period, as they were responsible for fully or co-sponsoring a whopping 38 of Alabama’s 57 monuments. According to the UDC’s current website, their organization seeks to “honor the memory of those who served and those who fell in the service of the Confederate state” and “to protect, preserve, and mark the places made historic by Confederate valor” (United Daughters of the Confederacy). Historians have argued, however, that, especially in its early years, the UDC went beyond simply honoring their Confederate ancestors. Karen Cox writes that the UDC perpetuated the social and cultural values of the Confederacy (including slavery and white supremacy) and became active agents in what she labels “the politics of vindication” (Cox, 2003). The UDC sought to provide the “true” history of the Confederacy, which often times avoided slavery and perpetuated the Lost Cause. It is reasonable to argue that racial ideas influenced the UDC in their push for monumentation.

One cannot deny the relationship between early 20th century racial ideas and Confederate monumentation, but race is by no means the only driving force behind the erection of Confederate monuments. As noted earlier, another likely reason for the rapid monumentation efforts at the beginning of the 20th century was Alabamians’ desire to honor the martial valor of their ancestors and to help themselves cope with the loss of so many Alabamians in battle. Another significant factor was the turn of the century, which saw a rapidly decreasing veteran population. As the war’s semicentennial (1911 – 1915) approached, the loss of so many local fathers, sons, and brothers likely weighed heavily on the minds of many Alabamians– especially those families who had not been able to retrieve the bodies of loved ones from distant battlefields. These monuments then, came to serve as tangible reminders of their family’s and community’s sacrifice to the Confederacy. In addition, these monuments provided communal spaces that allowed for loved ones and neighbors to come together to grieve and heal. Such factors might help to explain why many more monuments are dedicated to common soldiers than specific honorees in Alabama. Also, in the early 20th century, there was a growing fear among Southerners that the memories and values of the Confederacy, and antebellum South at large, would be lost with the passing of Confederate veterans. Thus, to preserve these memories and values, in addition to teaching younger generations about the war, Southerners sought to memorialize and vindicate the Confederacy through monumentation.

Funding also played a role in the timing of monumentation in Alabama. In the immediate years after the Civil War, most Southerners did not have the financial capacity to erect monuments (Mauldin, 2017). However, as the 20thcentury approached, Southern fortunes had recouped enough amongst more influential members of society (often politicians or large-scale farmers who were themselves frequently Confederate veterans) to be able to afford monumentation; this phenomenon coincides with the first flurry of monument building in Alabama (1890-1919). The patriotic fervor that swept the nation during this time, as a result of the Spanish American War and WWI, might also have played a role in Confederate monumentation. Alabamians may have been drawing martial inspiration for these conflicts from their Confederate ancestry.

This first wave of monumentation peaked in the first decade of the 20th century and by the 1930s had all but ended. As Americans moved further and further away from the war years and those who had lived during the war eventually died off, it makes sense that monumentation would decline significantly. However, five monuments were erected in the 1930s alone, which is intriguing given the onset of the Great Depression. One would think that the Depression would have placed such a financial strain upon Southerners (as it did to all Americans) that Alabamians would not have had the means to erect five monuments. It is also intriguing that between 1940 and 1989, there were only six monuments erected, but between 1990 and 2010, seven monuments were put up. This phenomenon requires further analysis, as the Cold War, modern Civil Rights movement, and Civil War Centennial all occurred during this time period and appear to have at least partially driven flurries of monumentation in other states.

The more recent uptick in monumentation is also curious. The seven monuments erected from 1990 to 2010 outnumber the monuments erected in the previous five decades combined (1940-1989). Multiple reasons might explain this recent surge, such as renewed interest sparked by the 1980s 125th anniversary of the war and anticipation of the Civil War Sesquicentennial, or improved financial prospects among certain influential groups or politically backed organizations within the state. Five of these seven monuments were either entirely or partially sponsored by the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV). The UDC sponsored one monument and co-sponsored another one. In addition, the Military Order of the Stars and Bars sponsored one monument. Six of the seven monuments are dedicated to common soldiers while the other monument is dedicated to General Joseph Wheeler, who served as a Democratic member of the House of Representatives from Alabama. The monument dedicated to General Wheeler is located in Joe Wheeler State Park in Rogersville. Following the war, General Wheeler settled in the Hillsboro area, which is roughly 30 miles from Rogersville.

As the map shows, these seven monuments are spread throughout the state, but exist mostly in rural areas, in towns with populations ranging from 1,200 to 35,000. Similar to these most recent monuments, a majority of Alabama’s 57 total Confederate monuments exist in lesser populated areas, spread across the state in 45 different locales. Montgomery is home to five monuments, which is the most of any city and makes sense, given the city’s history as the first Confederate capital. 34 of Alabama’s 57 monuments are located in cities with populations of 35,000 or less. The placement of monuments in more rural areas may result from numerous factors. Alabamians living in more rural areas may have stronger and deeper familial ties to these areas, which means that Confederate ancestry may be more prevelant there. Urban Alabamaians, who represent a more transient polulation, may not have as many deep familial ties to the area and thus lack Confederate ancestry or strong ties to Alabama’s Confederate past, which could explain why there are fewer Confederate monuemnts in urban areas. Also, the push for Confederate monuments in rural Alabama, especially the most recent ones, may well have been partially in response to the urbanization and moderinzation that has occurred throuhgout much of the South—including sections of Alabama–in the last century. These monuments might represent a more traditional worldview of local Alabamians who seek to cling to the southern past and southern traditions even more strongly in the face of such rapid growth and change.

Conclusion

Alabama’s Confederate monuments provide us with insights into the creation and maintenance of historical memory in the postbellum Deep South. A vast majority of Alabama’s monuments are dedicated to the common soldier, but specific individuals are represented. All of the specific individuals represented are either prominent Confederate leaders memorialized throughout the South or they have specific ties to Alabama. Alabama experienced rapid monumentation in the first decades of the 20th century, with curious, sporadic mini-bursts of additional monumentation throughout the rest of the century, including a relatively recent mini-flurry within the last 30 years. Without the UDC or the SCV, Alabama’s monument landscape would be much sparser. The UDC and SCV combined have sponsored 44 of Alabama’s 57 monuments, the UDC being responsible for 38 of them.

Both sides of today’s contentious Confederate monument debate have valid arguments, but they tend to homogenize Confederate monuments and overlook the complexities and nuances they have. These maps and this report attempt to explore some of these complexities and nuances by analyzing the location, origin, and erection date of these monuments. Each Confederate monument is unique in its erection date, place, and sponsors. While certain patterns are undoubtedly evident in suggesting causality and motive, it is vital to also keep in mind the individual context of each monument and to remember that temporal correlation does not always equate to causation.

This project does have its limitations as it solely focuses on monuments and does not consider schools, roads, building, towns, etc. that are named after Confederate leaders. In addition, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s data is crowdsourced and thus imperfect and incomplete. However, it helps to shed light on and offer new perspectives to the Confederate monument debate, while also reminding us that we still have many questions to pursue in order to more fully understand the meaning and memory of Confederate monuments in the past as well as the present.

Works Cited

Alabama Department of Archives and History. “Alabama History Timeline.”

https://archives.alabama.gov/timeline/al1861.html.

Alabama Department of Archives and History. “Official Symbols and Emblems of Alabama.”

Last modified Feb. 6, 2014. https://archives.alabama.gov/emblems/st_flag.html.

Alabama Historical Commission. “Monument Preservation Requests.”

https://ahc.alabama.gov/MonumentPreservation.aspx.

Cox, Karen L. Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the

Preservation of Confederate Culture. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2003.

Feldman, Glenn. Politics, Society, and the Klan in Alabama, 1915-1949. Tuscaloosa: University

of Alabama Press, 1999.

Gallagher, Gary W. “Leave them Standing: Confederate Monuments must remain at Gettysburg

to help Interpret the Civil War’s Causes and Consequences.” HisotryNet LLC. August

2020. https://www.historynet.com/leave-them-standing-confederate-monuments-must-

remain-at-gettysburg-to-help-interpret-the-civil-wars-causes-and-

consequences.htm?fbclid=IwAR1vo0qXspl72RxNAv94QbYVZ2ebYtRL93Z_nR7bzGW

Y5rC9skEwdSDX-kM.

Janney, Caroline E. Burying the Dead but no the Past: Ladies Memorial Associations and the

Lost Cause. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Mauldin, Erin Stewart. “Freedom, Economic Autonomy, and Ecological Change in the Cotton

South, 1865-1880.” Journal of the Civil War Era 7, 3 (September 2017): 401-424.

United Daughters of the Confederacy. “History of the UDC.” https://hqudc.org/history-of-the-

united-daughters-of-the-confederacy/.

Table 1: Data Sources

| Name | Creator | Date Valid For | Description | Hyperlink |

| Alabama Counties | T.I.G.E.R. | 2019 | Shapefile representing Alabama’s counties. | Link |